Segregated in the Heartland

In Springfield – and in cities across the country – government policies keep racial segregation in place

[

{

"name": "Air - MedRect Combo - Inline Content 1",

"component": "11490391",

"insertPoint": "3",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "1",

"parentWrapperClass": "fdn-ads-inline-content-block"

},{

"name": "Air - MedRect Combo - Inline Content 2",

"component": "11490392",

"insertPoint": "7",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "5",

"parentWrapperClass": "fdn-ads-inline-content-block"

},{

"name": "Air - MedRect Combo - Inline Content 3",

"component": "11490393",

"insertPoint": "12",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "9",

"parentWrapperClass": "fdn-ads-inline-content-block"

}

]

It didn’t take Silas Johnson long after he moved to Springfield to identify the border that separates the black section of the city from the white one.

Growing up in Mississippi as the civil rights movement swept through the South, Johnson knew about dividing lines. In the town of Macon, blacks knew to stay on their side of the railroad tracks. “It wasn’t something that was taught,” he says. “It was just something that was known.”

After he graduated high school in 1973, Johnson left the South to join his brother in Springfield, the state capital and former home of Abraham Lincoln. But Johnson soon discovered that race relations in his new home weren’t much better than what he’d left behind. Blacks and whites attended separate schools. Blacks were excluded from certain professions.

And just like Macon, Springfield cleaved in two along racial lines, with railroad tracks again marking the split. This time, it was the Norfolk Southern tracks alongside Ninth Street. East of the tracks, the neighborhoods were predominantly black, and many blocks were pockmarked by vacant houses and boarded-up businesses. West of the tracks, the neighborhoods got progressively whiter and wealthier. “I experienced a lot of racism here. It was more covered up than it was open,” says Johnson, now 63, pastor of Calvary Missionary Baptist Church and president of the nonprofit Faith Coalition for the Common Good. “In the South, blacks stayed in certain areas and so did whites. That’s the same here now in Springfield.”

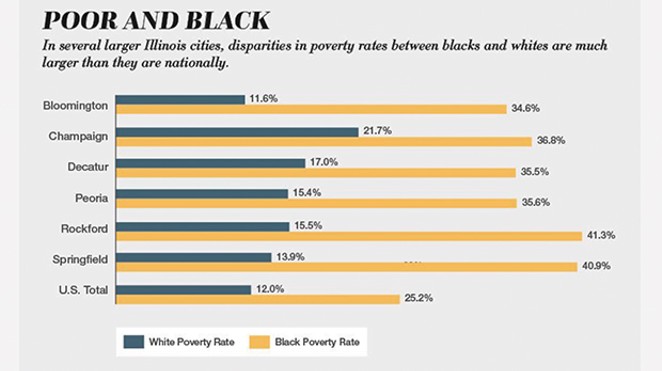

That pattern persists in cities throughout the state. In fact, according to a new Governing investigation, segregation between blacks and whites is worse in most of Illinois’ metropolitan areas than in demographically similar areas around the country. It’s particularly bad in large metro areas, and certainly the Chicago region is the most segregated in Illinois. But the state’s smaller cities are also disproportionately segregated.

Springfield may have launched the political careers of Lincoln and Barack Obama, but it is among the worst third of American cities in terms of black-white segregation, according to our analysis of federal data. Both the Springfield and Champaign-Urbana metro areas are more segregated than that of Charlottesville, Virginia, or the Daphne-Fairhope-Foley area near Mobile, Alabama, even though they all have similar populations and percentages of black residents. The truth is that segregation isn’t limited to the South, or to large cities. America’s racial divide, in fact, runs right through the Heartland.

Governing conducted a six-month investigation into segregation in downstate Illinois, and why and how it has persisted there. We spoke with more than 80 people, including mayors and other city officials, legislators, sociologists, attorneys, school district officials, historians, community activists, housing experts and both black and white residents. We analyzed 50 years’ worth of U.S. Census data for economic and demographic trends, along with both state and federal school enrollment data. We also drew from hundreds of pages of court documents, information obtained through Freedom of Information Act requests, several books and dozens of academic reports. This is an abridged version of the first article in the series. The complete article is available at illinoistimes.com.

What emerged was a picture of the way segregation continues to shape and reshape metropolitan areas in Illinois and, indeed, throughout many parts of the country. In these cities, segregation means not just a physical divide, but a huge disparity in resources. White areas of town benefit from more development, better infrastructure and more accommodating government policies.

What’s more, we found local governments bear much of the responsibility for creating and maintaining segregated communities. Mayors and other city officials are often focused on immediate concerns, such as balancing tight budgets or attracting economic development. While those are legitimate, pressing issues, the resulting policies can often reinforce segregation. Through unspoken traditions and ingrained attitudes, as well as explicit government actions, city officials are in many ways responsible for maintaining a system that still divides whites and blacks.

When it comes to land use – what gets built where – governments use zoning restrictions to keep out rental housing, which attracts blacks and other minorities, from predominantly white areas. They approve new residential subdivisions with strict deed restrictions that make large swaths of communities unaffordable to low-income residents and often explicitly bar any use other than single-family homes. As they restrict where apartments can be built, local governments also play a big role in deciding where public housing and other taxpayer-supported affordable housing projects are located. That often leads to concentrated areas of low-income housing in black neighborhoods. Those changes almost inevitably become permanent, because the income restrictions and other rules that come with public subsidies last for decades.

Finally, residents in predominantly black neighborhoods routinely face more scrutiny from police and other government agencies, which reinforces the patterns of segregation that have already emerged. Government actions such as increased code enforcement, zero tolerance policies for drugs in public housing and disproportionately targeting black neighborhoods for traffic stops result in black residents facing more municipal fines or other minor punishments.

Wrong side of the tracks

While people may associate segregation with the Jim Crow-era South, the truth is that the most segregated metropolitan areas today, in terms of where people live, are in the industrial Midwest and the Northeast, the destinations for most blacks fleeing the South during the Great Migration of the 1900s. The cities of those regions established housing patterns that persist today, especially where economic troubles have made new growth and investment difficult.

Nationally, overall levels of segregation have fallen in recent decades. That’s especially true in cities and other small geographic areas, like suburbs or school districts. Blacks and whites are slightly more likely to live in the same neighborhoods than they were in the 1980s.

But that’s not the whole story. A more troubling pattern emerges when you widen the scope to look at entire metropolitan areas, focusing not just on individual cities or suburbs but looking at cities and their suburbs together. Instead of moving to different areas of the same city, whites are moving farther away to suburbs and exurbs. That’s why, measured at the metro level, progress toward more racially integrated neighborhoods over the past few decades looks decidedly less impressive. In fact, in the metro areas for Peoria, Danville and Champaign-Urbana, the degree of segregation remains roughly as high as it was in 1980. It’s that metro area measure by which the Peoria area ranks as the sixth most segregated in the nation.

Sociologists commonly measure segregation by calculating what’s known as a dissimilarity index. That shows what percentage of, for example, whites would have to move to black neighborhoods for them to live in a neighborhood that would have the same black-white ratio as the area as a whole. Governing calculated that measure to show the degree of segregation both in metro areas and in their schools.

Illinois has several other highly segregated metropolitan areas. Danville, a small city near the Indiana border, is the 12th most segregated place in America with at least 10,000 black residents. Along with Springfield, Kankakee and Rockford are among the worst third. (The Governing analysis was confined to segregation between blacks and whites, because the number of Hispanics and Asians living in most downstate Illinois cities is relatively small.)

Perhaps no Illinois city displays its segregation more plainly than the capital of Springfield itself. “You see it when you cross that invisible dividing line,” says Teresa Haley, the president of both the Springfield branch and the state chapter of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP).

One way to see it clearly is to drive along South Grand Avenue, a major east-west thoroughfare that cuts across the city. Starting on the east side, you’ll find Springfield’s poorest – and most heavily black – neighborhoods. Some blocks contain tidy, modest houses, but many are ramshackle. The streets are poorly lit, and they often lack curbs, sidewalks and gutters. In three east side neighborhoods, about half the households live in poverty, according to the most recent data. The unemployment rate across those three neighborhoods is 24 percent. Life expectancy in two of the neighborhoods is 70 years old or below, compared with nearly 79 years nationally. Overall, the five-census-tract area covering the east side is 65 percent black, but in some neighborhoods it’s as high as 80 percent.

Drive west on South Grand, under the viaduct carrying the Norfolk Southern tracks, and things immediately begin to change. On the largely white west side, just a mile and a half away, South Grand is covered by a canopy of trees as it makes its way past blocks of stately brick houses, many of them mansions on enormous lots. The street itself narrows and then disappears completely into Washington Park, 150 acres of rustling trees and rolling hills graced with a carillon, a rose garden, fishing ponds and a popular running path. Two golf courses adjoin the park. Also nearby is Leland Grove, a village of 1,500 people surrounded by Springfield. It’s an enclave within an enclave, where the median household income is double that of the rest of the city. According to the Census Bureau, the population of Leland Grove is 95 percent white and 1 percent black.

Beyond that, Springfield keeps sprawling west. Residents in new subdivisions can see combines and grain elevators from their driveways. Commercial development has been in hot pursuit: Restaurants, dentists, banks, hair salons and a Walmart have opened up, not to mention the churches, schools and parks that inevitably follow wherever people move. “With Springfield,” says Mayor Jim Langfelder, a banker by trade, “everybody wants to go west. They want to go where the numbers are, where the incomes are. With the east side, though, it’s a struggle. You have pockets of development, but there’s still a lot more to go.”

Of course, many of the symbolic racial borders in Springfield and other cities have been codified in official ways, with real-world consequences. Perhaps the best-known examples of that are the “redlining” maps first drawn by the federal government during the Great Depression. As part of the New Deal, Congress introduced new federally backed mortgages that were intended to make home loans more affordable for middle-class families for the first time. To keep from losing money on the loans, the federal government hired real estate agents in 239 cities to draw maps designating where the most “creditworthy” residents lived. Areas deemed high-risk were outlined in red. As a rule, the agents drew bright red lines around any minority neighborhoods. Thus, whites were able to buy new homes, build wealth and pass along that wealth to their families. Blacks could not get credit to even maintain or improve their existing properties. Their neighborhoods suffered as banks and businesses fled, buildings deteriorated and outside landlords scooped up the distressed properties so they could rent them out. Those policies have had a long-lasting effect at the individual level as well. To this day, 62 percent of black households in Illinois rent their homes, compared with 27 percent for whites. The 1968 Fair Housing Act and subsequent federal laws ended legally sanctioned redlining, but the patterns from those maps persist today.

White flight continues

Increasingly, the disparities caused by racial segregation aren’t within local jurisdictions but between them. Just look at downstate Illinois schools. The core urban school districts in Bloomington, Champaign, Urbana, Springfield and Decatur – all still predominantly white cities – had majorities of white students in the 2002-2003 school year. Now, none of them do. Over the same period, the share of white students in Rockford Public Schools also dropped, from 48 percent to 30.

Urban districts are losing white students far faster than their metropolitan areas at large. Decatur Public Schools, for example, lost 38 percent of its white students in the last 15 years, but the rest of the metro area only lost 7 percent of its white students. By comparison, the district lost just 11 percent of its black students in the same time frame.

Peoria provides the starkest example. The main school district there has fewer than half of the white students it had 15 years ago, but the decline in white students for all of the other school districts in the metro area was less than 8 percent.

In other words, white flight to suburban areas is drastically altering the makeup even of small metropolitan areas in Illinois. Once-sleepy farm towns are now attracting residents by the hundreds. In a bid that’s familiar to suburbanites in bigger metro areas, these hamlets market themselves as both conveniently close to the job centers in nearby cities and as distinct from them. “With excellent schools, a low crime rate and beautiful natural parks, Roscoe is the perfect place for your business, family and home,” crows the website of Roscoe, a village of 10,500 people north of Rockford that’s close to the Wisconsin border. From 1990 to 2010, the white population there tripled from 2,326 people to 9,544. Meanwhile, the number of black people in the village grew from 13 in 1990 to 325 in 2010. Chatham, a village just south of Springfield, touts the motto “Family, Community, Prosperity.” It saw its white population grow by 4,356 people over those two decades, while it added 265 black residents.

The outflow is having a major impact on core cities. Since 1970, the cities of Decatur, Peoria and Rockford lost between 25 and 40 percent of their white residents, while surrounding jurisdictions within the same regions collectively added white residents. At the same time, black residents are moving into older, traditionally white neighborhoods in many of those cities. In three neighborhoods just north of downtown Peoria, for example, a total of more than 3,400 white residents have moved out since 2000, while the number of black residents increased by nearly 2,000.

The popularity of the farther-out enclaves puts big-city leaders in a bind: They can either compete with the suburbs by annexing new subdivisions and strip malls carved out of farmland, or they can lose that tax base to nearby suburbs that are only too happy to take it off a city’s hands.

Meanwhile, local governments in predominantly white areas have made it difficult for many blacks to move to the areas of new development. Very few of the predominantly white suburbs that have sprung up in recent decades allow for apartment-style multifamily units to be built within their borders. The lack of rental choices disproportionately affects black residents, because, again, they are more than twice as likely to rent their home as whites. The housing stock determines where they can live.

One neighborhood at a time

Bringing affordable housing to Springfield’s east side is exactly what Silas Johnson is trying to do, and he’s already made a lot of progress.

Johnson made a good living as an electrician. He went to work for the city, and eventually saved up enough money to buy a house. But in 1984, when he was 29, Johnson took on another job, too, as pastor of Calvary Missionary Baptist Church on the far east side. He saw firsthand what decades of disinvestment had done to the immediate neighborhood around the church. Clutter and tall weeds filled vacant lots. People were dealing drugs across the street, and the houses next door were rundown eyesores.

He knew he needed to act. “In order to control your neighborhood, your area, you need to own stuff around you,” he says. “You can’t wait on everybody else.”

The church started acquiring property, so it could have the trees trimmed, the grass cut and the drug-dealing eliminated. Johnson also created a nonprofit to buy rundown houses from absentee landlords, fix them up and sell them to neighborhood residents at a low price.

The nonprofit’s original plan had some serious weaknesses. One reason why people hadn’t already been buying homes on the east side is because they couldn’t get a loan from the bank. Either their credit wasn’t good enough, or the banks didn’t want to invest in an east side property. One drawback to living in a predominantly black neighborhood is that property doesn’t hold its value well there, because whites generally don’t want to live there, lowering the property’s marketability. The other reason was the homes themselves. Not only were they old, but, because they were old, they tended to be small and crowded onto lots just 40 feet wide. The city of Springfield started mandating that lots be at least 60 feet wide in 1966, but the houses predated that requirement.

So Johnson worked with a developer to come up with a different approach. The nonprofit, Nehemiah Expansion, would build its own single-family houses using the federal low-income housing tax credit. The tax credit allows corporations and other big taxpayers to reduce their taxes by funding affordable housing through credits bought from state agencies. The states then distribute the money they raise to projects on a competitive basis.

What that means is that it costs Nehemiah substantially less to build new housing. The nonprofit also borrows money at low interest rates from the Illinois Housing Development Agency (IHDA), which it pays back using the rent paid by occupants. And the city and other creditors agree to remove the liens they hold against some of the vacant homes, sometimes using the in-kind contribution as a tax write-off.

As for the houses, Nehemiah looks for places it can buy three 40-foot-wide lots next to each other and split them into two 60-foot-wide lots. That’s enough to build one of five models of houses, with anywhere from two bedrooms to four bedrooms, a laundry room and a one-car garage.

But the real impact of the houses comes at the end of 15 years, when they’re permitted to go on the market. The renter in the unit gets first dibs, and he or she only has to pay what Nehemiah owes IHDA, but not the cost covered by the tax credit. The theory is, in other words, that occupants could buy a $70,000 house for $50,000. That would give the buyer instant equity, something that’s long been in short supply in black neighborhoods, and signals to the market that homes can sell on the east side.

Nehemiah has built 80 new homes so far, with plans for more. The first batch of 20 homes will go on sale in about three years. Most of Nehemiah’s renters are black, although several are white. “When we started this project, [this area] was 75 percent rental, 25 percent owner-occupied housing,” Johnson says. “My goal is to reverse that whole trend, to go back to being 75, 80 percent owner-occupied.”

It’s certainly an ambitious goal, considering just a third of people in surrounding neighborhoods own their own homes. But it seems to be one that’s paying off already. For several blocks on the east side of Springfield, resources available to black residents such as quality housing and perhaps even home equity seem to be slowly building, rather than constantly draining as a result of racial segregation.

This is an edited excerpt from Governing’s four-part series on segregation in downstate Illinois. For a link to the full article, go to illinoistimes.com.

About the article

Governing magazine, based in Washington, D.C., covers state and local government across the country – the laws and leadership that shape the way states and cities serve their citizens. The magazine decided to devote attention to the ongoing issue of residential segregation in America, and how government policies continue to reinforce the racial divide between blacks and whites. Staff writer Daniel C. Vock, an Illinois native and a former Statehouse reporter in Springfield, began looking at the issue in several downstate Illinois cities. It’s easy to think of segregation as something most prevalent in the South, or in large urban areas. But parts of downstate Illinois are among the worst metro areas in the nation for residential and school segregation. The focus on this part of Middle America provided a lens on this crucial issue throughout the country.

Vock, along with Governing staff writer J. Brian Charles and data editor Mike Maciag, spent six months investigating and reporting this special series. Together with a photographer, the team spent a combined 20 days reporting on the ground in Illinois, including six days altogether in Springfield.

Illinois Times has provided readers with independent journalism for almost 50 years, from news and politics to arts and culture.

Your support will help cover the costs of editorial content published each week. Without local news organizations, we would be less informed about the issues that affect our community..

Got something to say?

Send a letter to the editor and we'll publish your feedback in print!