Conversations with William Maxwell, edited by Barbara Burkhardt. University Press of Mississippi. (Literary Conversations Series) 241 pages. Hardback, $40.

When Barbara Burkhardt, an associate professor of English at the University of Illinois Springfield, published her biography of William Maxwell in 2005, reviewers were justifiably enthusiastic. Maxwell, who spent his early years in Lincoln, Ill., in which he set many of his fictional works, died in New York in 2000, at the age of 92, after a career that produced an impressive array of novels, stories, fables and letters, many of the latter in exchanges with the legendary writers he worked with in his 40 years as a fiction editor at The New Yorker. Burkhardt’s William Maxwell: A Literary Life captured the spirit and style of this consummate literary craftsman.

In the New York Times Book Review, Morris Dickstein said that Burkhardt’s work “rises splendidly to his best novels and stories,” which is high praise indeed, since those novels and stories are almost universally admired among serious readers and writers.

Bill Savage, in the Chicago Tribune, paid tribute to Burkhardt’s “deeply layered, supple, and clean prose,” in which she captured “the drama of Maxwell’s life.” Both reviewers, along with luminaries like John Updike, believed that Burkhardt’s work was worthy of Maxwell’s achievements, and the implicit hope was that her effort might bring more readers into the Maxwell fold.

And now comes another effort by Burkhardt to spread the word about the quiet life and estimable work of one of the great under-appreciated authors of the 20th century. Burkhardt has edited Conversations with William Maxwell, a compilation of 29 disparate items which, together, provide a detailed impression of his literary influences, his goals and motivations, his generous, compassionate character, and his unassuming personality. It’s part of the University Press of Mississippi’s “Literary Conversations Series,” which includes similar compilations for scores of writers, from Wendell Berry to Ursula K. LeGuin to Gore Vidal, Pauline Kael and David Foster Wallace.

Burkhardt’s introduction lays the groundwork for the collection, deftly emphasizing the qualities that so many of his interviewers and commentators note in Maxwell’s work – a “bare, elegant style: the kindly, sensitive voice balanced with intellect and emotional steel.”

The matter of style is addressed repeatedly in the interviews, speeches and articles which comprise this volume. Maxwell reiterates his quest for the simplest and most direct way of expressing himself, and he extols the “clean, decent sentence” as the fundamental building block of good writing. He asserts the primacy of the sentence in his interviews with Burkhardt in the early 1990s, and also in his 1981 Paris Review interview with George Plimpton and John Seabrook. He sometimes clips sentences from his drafts, he says, when he thinks they don’t belong, and keeps them to use in future works, where they fit more comfortably.

The details of his nearly accidental start at the magazine, hired by Katharine White as an art editor, are rendered in a number of pieces, as interviewers over the years caught up with Maxwell’s achievements and retold his story for new generations of readers. Discussions about whether there is a New Yorker style (Maxwell denies there is) are mixed with anecdotes about his work “seeing the artists” (i.e., telling the cartoonists whether their pictures had been bought) and his relationships with colleagues like E.B. White and James Thurber, and with the legendary editors, Harold Ross and William Shawn, under whom he worked in his 40 years at the magazine.

But his relationship with his Midwestern past, in Lincoln, Chicago and Urbana-Champaign, is perhaps the most persistent subject in the varied pieces in the collection. His childhood in Lincoln, where his mother died in the influenza epidemic of 1918; his adolescence in Chicago, where he attended Senn High School; and his college years and, later, his two years as an instructor at the University of Illinois, are rendered beautifully in works like The Folded Leaf (1945) and So Long, See You Tomorrow (1980), his two most highly acclaimed novels, and in many of the short stories which first appeared in The New Yorker.

The first selection in the book, based on handwritten notes from a talk Maxwell made at Smith College in 1955, reveals much about Maxwell’s writing process. He compared the writer to a magician, who “must begin by pleasing himself,” by letting his characters develop their identities and fulfill their destinies without interference. It was at that symposium that Saul Bellow made a remark that made a lasting impression on Maxwell: “A writer is a reader who is moved to emulation,” said Bellow, and it became a kind of mantra for Maxwell when he was asked about what it took to be a writer.

Many of the other interviews and articles provide insights into those writers who influenced Maxwell. A forgotten writer like Zona Gale, an early mentor to Maxwell, is mentioned repeatedly, always with respect. To varying degrees, he found writers as disparate as Henry James, E.B. White, Willa Cather, E.M. Forster and Colette influential. He admired poets, too, like William Meredith, Edward Arlington Robinson and his close personal friend Robert Fitzgerald, who went from Springfield High School to Harvard and became a celebrated poet and one of the century’s most influential translators.

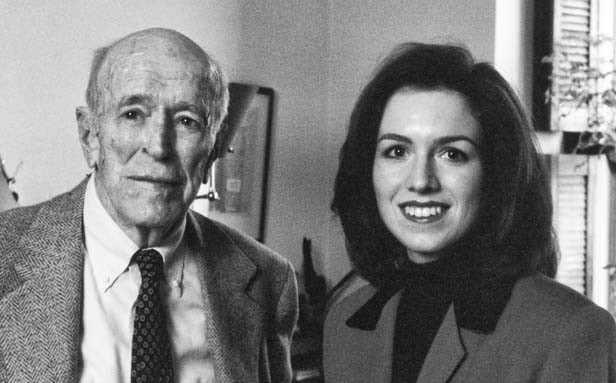

Burkhardt’s graduate studies, first at UIS (disclosure: I served as her advisor when she earned her M.A., in which role I applied Maxwell’s principle of just not getting in the way) and later at the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign, where she earned her PhD, enabled her to pursue her interest in Maxwell and led to the three hitherto unpublished interviews which hold down the center of this collection. Between 1991 and 1993, Burkhardt and Maxwell had conversations which ranged widely, over literary topics and his political and religious beliefs (liberal Democrat and atheist), but also over subjects as mundane as his preferences in music, modes of travel, and food (“moussaka, lamb shanks, sweet corn, fish stuffed with fennel” and more, in case you’re curious).

A collection like this is bound to be uneven, including as it does sit-down interviews (at some of which Maxwell typed out answers for his interlocutors), some brief speeches of Maxwell’s in praise of other writers (which demonstrated his generosity of spirit) and newspaper articles. Burkhardt’s interviews stand out, along with the one from the Paris Review and another from Tamaqua, a literary journal, and ones by Kate Bonetti, David Stanton and the poet Edward Hirsch. Others (an interview on KMOX radio, for example) contributed little and might better have been left out. But the solid ones convey much about Maxwell’s personality and values, and a reader comes away with a fresher sense of the man behind the six remarkable novels and other writings which trickled out over the 60-plus years of his writing life, starting with the novel Bright Center of Heaven in 1934, through collections of stories and children’s tales in the 1990s.

Because each interviewer over these many years is, in a sense, giving a new set of readers an introduction to a writer who may be fairly new to them, there’s some inevitable overlap among them. They have to ask Maxwell to talk about Lincoln, about his mother’s death, about his favorite authors, and about his writing methods. In her introduction, Burkhardt observes that “the author occasionally remembers things differently in subsequent interviews.” But I was struck by how consistent his anecdotes were, down to the smallest details. He talks at least three times, for example, about his first paid writing assignment, which came through his landlady in Champaign, when he was an English instructor at the university. He renders the story of Lady Jane Coke, an eccentric English noblewoman, about whom he wrote a summary, with exquisite precision, down to the way she “dressed her servants in pea-green livery” and “used to fish in the ornamental goldfish pond.” He uses almost the same words, in the same phrases in at least three separate interviews over 14 years, a tribute to his memory.

That attention to detail was the hallmark of Maxwell’s writing, throughout his long and illustrious career. He was drawn, he said, “to examine the significance of small things out of a distaste for the grandiose.” Demonstrating the “significance of the insignificant,” as George Eliot once put it, is no small challenge, and William Maxwell’s work is a testimony to its worthiness. While Barbara Burkhardt’s Conversations may not lure masses to Maxwell’s fold – the novels and stories would have to do that – it will deepen the understanding of those who’ve already discovered this “American Chekhov,” as the poet Edward Hirsch has so fittingly called him.

After Rich Shereikis retired from the English program at Sangamon State, he and his wife, Judy, have divided their time between Evanston, Ill., and Washington Island, Wis., where Rich serves as chair of the editorial committee of the town’s weekly newspaper. His first encounter with William Maxwell came when he reviewed So Long, See You Tomorrow for Illinois Times, where he moonlighted for nearly 20 years as movie reviewer, columnist and feature writer. After doing the review, he made So Long a regular part of his course on the Midwestern novel.