He began roofing at the age of 13, his family says, and was once employed by the same company for nine years. He didn’t have a driver’s license owing to a driving under the influence conviction. If he couldn’t catch a ride to work, he’d call a cab.

“He was early, if anything,” recalls his employer, John Muehlebach, owner of Muehlebach Roofing. “He’s the type of employee you don’t come across very often in my industry.”

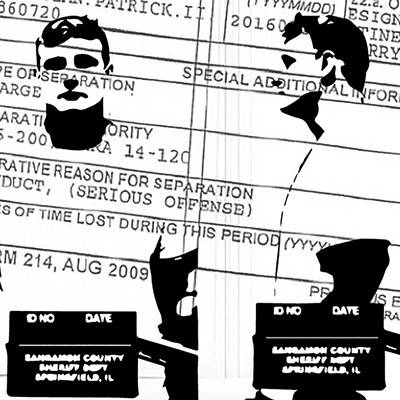

In 1998, Kendall was convicted of burglary and sent to prison for five years, a byproduct, his relatives say, of a problem with crack cocaine that he ultimately overcame. Besides drunken driving convictions, he has since had two misdemeanor convictions for damaging property and a misdemeanor conviction for resisting police. Not a stellar record, to be sure, but he was hardly public enemy number one. Muehlebach remembers him as quiet. Trustworthy. Dependable. His relatives describe Kendall as an imperfect guy who liked to work, drink beer and smoke pot.

On Dec. 6, 2012, robbers broke down Kendall’s front door, tied him up and threatened to shoot him while demanding money and marijuana, according to a police report taken after Kendall called 911. He exhibited symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder, according to at least one expert, and he told friends and relatives that he feared the robbers would return and kill him. He got an estimate from an alarm company, barricaded his door with two-by-fours and filled out a FOID card application, even though he wasn’t supposed to have a gun because he was a felon. Nonetheless, he obtained a pistol.

One month after the robbery, a snitch told police that Kendall was armed and selling pot. As dealers go, Kendall was nickel and dime. The gun, Det. Chad Larner testified in court last week, was the main concern.

“What was conveyed to us by a confidential source was, we had a convicted felon, and he had a gun and he was sleeping with it at night,” Larner said.

Decatur police did what Decatur cops do in such situations. After a judge signed a search warrant, a SWAT team headed to Kendall’s house at 6:30 a.m. on Jan. 10, 2013.

Police knocked, announced their identity, then started to break down the door. In response, Kendall fired a single shot through the closed door. The bullet hit at doorknob level before striking officer Jason Hesse in the ankle. During trial in July, Kendall testified that he aimed the way he did because he wanted to scare, not kill.

After firing, Kendall promptly called 911 to report that he was again being robbed. When the dispatcher told Kendall that police, not robbers, were on his porch, he opened his door and apologized. The cops found an ounce-and-a-half of pot.

Prosecutors threw the book, charging Kendall with attempted murder, armed criminal violence, illegal gun possession and possession of marijuana with intent to distribute. They also asked the jury to find that Kendall had discharged a firearm that caused “great bodily harm.” If convicted on all counts, he was facing a de facto life sentence.

Even police thought it was overkill.

“From the very beginning…of this, I had reservations about our ability to show he intended to murder a police officer,” Larner testified last week during sentencing proceedings.

The jury didn’t buy it either and acquitted Kendall of attempted murder. In a separate finding, jurors also determined that prosecutors hadn’t proven that Kendall had fired a gun that caused bodily harm, even though he testified that he had pulled the trigger and the bullet was found in Hesse’s leg.

In short, the jury rejected the notion that Kendall had even fired a shot, and so the defendant escaped a mandatory minimum sentence of 25 years. But the other charges stuck, and armed criminal violence carries a minimum sentence of 15 years.

A person is guilty of armed criminal violence if he commits a felony while armed, and possession of marijuana with intent to distribute is a felony. If Kendall had acted like a criminal and flushed the pot down his toilet when the cops came, he might not be in such a mess. Instead, he opened his door, apologized and allowed police to pin him with a felony drug charge that paved his path to prison. He got a 22-year sentence, seven years more than the mandatory minimum, but 20 years less than prosecutors requested during last week’s hearing.

In pronouncing sentence, Macon County Circuit Court Judge Timothy Steadman declared that Kendall probably was afraid of robbers, but he might also have been trying to protect his drug dealing enterprise when he obtained a gun.

“The point is this: It’s illegal for a felon to possess a firearm under any circumstances,” Steadman said.

From afar, it looks like a case of bad policing to Stephen Downing, retired deputy chief of the Los Angeles Police Department who sits on the board of Law Enforcement Against Prohibition, a group of former cops and prosecutors who believe that the war against drugs is a failure.

The Los Angeles Police Department invented SWAT teams but does not routinely use them to serve search warrants in drug cases, Downing says. Given that Kendall didn’t have a violent history, the retired deputy chief says that the cops should have surrounded his house and either ordered him to come out or waited until he came out on his own and caught him unawares.

“What you’re talking about isn’t smart policing,” Downing says. “What you’ve got is a bunch of dummies that are not serving the community well. … I think that sometimes law enforcement is too overeager and their common sense is replaced by this militaristic ode, this warrior thing. The thing they forget is, their purpose is to preserve human life. We (police) are not the military.”

Los Angeles is a world away from Decatur, where police still use a SWAT team to bust suspected dealers and make no apologies.

“That may be how Los Angeles would do it,” says Decatur deputy chief James Chervinko when asked why his department doesn’t use tactics suggested by Downing. “However, with Decatur – and I speak for us and us alone – normally, if we receive a search warrant from a judge, we are going to make entry into the house and try to apprehend the subject before he can use the weapon against anybody. We’ve done hundreds over the years. This is one time when he shot out through the door.”

Contact Bruce Rushton at [email protected].