Cowboy Joe

A Sangamonian makes, and writes, history in the West

[

{

"name": "Air - MedRect Combo - Inline Content 1",

"component": "11490391",

"insertPoint": "3",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "1",

"parentWrapperClass": "fdn-ads-inline-content-block"

},{

"name": "Air - MedRect Combo - Inline Content 2",

"component": "11490392",

"insertPoint": "7",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "5",

"parentWrapperClass": "fdn-ads-inline-content-block"

},{

"name": "Air - MedRect Combo - Inline Content 3",

"component": "11490393",

"insertPoint": "12",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "9",

"parentWrapperClass": "fdn-ads-inline-content-block"

}

]

These days, a man who stands at the edge of Springfield and gazes at the wide open spaces to the west and imagines herds grazing contentedly is a shopping center developer. A century and a half ago, he was a cattle man looking for grass. Mid-Illinois once was America’s wide open spaces, and the landscape supported great herds of beef cattle being fattened on grass for the Eastern markets. That way of making meat takes time and a lot of pasture and it quickly proved to be uneconomic as demand for farmland pushed up the price of grassy land. Most Illinois cattlemen moved west in search of cheaper range.

One of those westward-looking men, I have learned, was Joseph G. McCoy. He was born and raised on a farm in western Sangamon County, one of 11 children. (Farmers bred stock too.) He went to Knox College for two years, but he was not a scholar. He married a Cass County girl and took up farming but the plow fit him no more naturally than did the book. He would later describe himself as “of that sanguine, impetuous, speculative temperament; just such dispositions as always look most upon the bright side of the picture and never feel inclined to look at the dangers or hazards of a venture, but take it for granted that all will end well that looks well in the beginning.”

He found his calling when he went into the business on the side shipping cattle with his brothers. It took a lot of beef to feed the Union Army, and by the end of the Civil War he was doing just fine, thank you, with as many as 3,000 head on the road at one time. The cattle by then were out West but the hungry mouths were back East. A steer worth $3 or $4 in Texas would fetch up to 10 times that in Chicago, but driving Texas longhorns east to the nearest rail depots became impossible. Texas cattle carried a tick from those parts that in turn carried a bovine disease called Spanish or Texas fever. Longhorns were immune to its worst effects but the disease decimated shorthorn herds elsewhere. Midwestern and Plains farmers refused to countenance Texas animals on their land, even in passage, and passed laws banning their movement.

McCoy’s genius was to realize that cows that weren’t allowed to walk across Kansas to the east could ride if someone set up a cattle depot in the unpopulated West from which trains then sped them directly to slaughterhouses in the East. He determined to be that someone. He bought a quarter-section outside Abilene in western Kansas, which was as yet uninfested with farmers. There McCoy bought his land from the owner of the saloon, “a corpulent, jolly, goodsouled, congenial old man of the backwoods pattern” who kept a colony of prairie dogs as pets and sold them to tourists. On it he built a hotel – the wonderfully named Drovers Cottage – stock pens, an office and bank on the new Kansas Pacific (later the Union Pacific) Railway, and advertised that cattle driven there could be sold at Eastern prices. (Howard Hawks’ 1948 movie Red River imagines the first drive that pulled, or rather walked, into Abilene.) Within a few years, 600,000 cattle a year were being moved to and out of Abilene from Texas.

Abilene was a dump that combined the boomtown with the cowboy town to the improvement of neither. McCoy was elected mayor, and locals soon realized what a subsequent generation of Illinoisans is only now learning, which is that successful businessmen do not make good public officials. McCoy ran the town as if he owned all of it and not just the important part. To keep the peace, he brought in superstar talent such as Wild Bill Hickok, who quickly shot his own deputy in a gunfight. I don’t know how much Hickok was being paid, but I’m sure he could have been making more in the private sector.

The boom didn’t last of course. Settlers were moving west toward Abilene, and that left no room in the area to rest and feed herds awaiting shipment. New Abilenes were built elsewhere. McCoy stayed out West, although he never built an empire, being essentially a middleman. He did make a lasting contribution to the region, but it was as a writer; his Historic Sketches of the Cattle Trade of the West and Southwest, published in 1874, has been called by at least one historian “the foundation for anything written about the cattle drive era.”

“It has been the Author’s lot in his brief life, to do, to act, and not to write,” reads his preface. “With a deep conviction that in the work a hundred errors and imperfections exist to each single merit, it is diffidently submitted to the reading, but not to the critic world.” He was mistaken about his book. Sangamon County’s loss was history’s gain.

Contact James Krohe Jr. at [email protected].

One of those westward-looking men, I have learned, was Joseph G. McCoy. He was born and raised on a farm in western Sangamon County, one of 11 children. (Farmers bred stock too.) He went to Knox College for two years, but he was not a scholar. He married a Cass County girl and took up farming but the plow fit him no more naturally than did the book. He would later describe himself as “of that sanguine, impetuous, speculative temperament; just such dispositions as always look most upon the bright side of the picture and never feel inclined to look at the dangers or hazards of a venture, but take it for granted that all will end well that looks well in the beginning.”

He found his calling when he went into the business on the side shipping cattle with his brothers. It took a lot of beef to feed the Union Army, and by the end of the Civil War he was doing just fine, thank you, with as many as 3,000 head on the road at one time. The cattle by then were out West but the hungry mouths were back East. A steer worth $3 or $4 in Texas would fetch up to 10 times that in Chicago, but driving Texas longhorns east to the nearest rail depots became impossible. Texas cattle carried a tick from those parts that in turn carried a bovine disease called Spanish or Texas fever. Longhorns were immune to its worst effects but the disease decimated shorthorn herds elsewhere. Midwestern and Plains farmers refused to countenance Texas animals on their land, even in passage, and passed laws banning their movement.

McCoy’s genius was to realize that cows that weren’t allowed to walk across Kansas to the east could ride if someone set up a cattle depot in the unpopulated West from which trains then sped them directly to slaughterhouses in the East. He determined to be that someone. He bought a quarter-section outside Abilene in western Kansas, which was as yet uninfested with farmers. There McCoy bought his land from the owner of the saloon, “a corpulent, jolly, goodsouled, congenial old man of the backwoods pattern” who kept a colony of prairie dogs as pets and sold them to tourists. On it he built a hotel – the wonderfully named Drovers Cottage – stock pens, an office and bank on the new Kansas Pacific (later the Union Pacific) Railway, and advertised that cattle driven there could be sold at Eastern prices. (Howard Hawks’ 1948 movie Red River imagines the first drive that pulled, or rather walked, into Abilene.) Within a few years, 600,000 cattle a year were being moved to and out of Abilene from Texas.

Abilene was a dump that combined the boomtown with the cowboy town to the improvement of neither. McCoy was elected mayor, and locals soon realized what a subsequent generation of Illinoisans is only now learning, which is that successful businessmen do not make good public officials. McCoy ran the town as if he owned all of it and not just the important part. To keep the peace, he brought in superstar talent such as Wild Bill Hickok, who quickly shot his own deputy in a gunfight. I don’t know how much Hickok was being paid, but I’m sure he could have been making more in the private sector.

The boom didn’t last of course. Settlers were moving west toward Abilene, and that left no room in the area to rest and feed herds awaiting shipment. New Abilenes were built elsewhere. McCoy stayed out West, although he never built an empire, being essentially a middleman. He did make a lasting contribution to the region, but it was as a writer; his Historic Sketches of the Cattle Trade of the West and Southwest, published in 1874, has been called by at least one historian “the foundation for anything written about the cattle drive era.”

“It has been the Author’s lot in his brief life, to do, to act, and not to write,” reads his preface. “With a deep conviction that in the work a hundred errors and imperfections exist to each single merit, it is diffidently submitted to the reading, but not to the critic world.” He was mistaken about his book. Sangamon County’s loss was history’s gain.

Contact James Krohe Jr. at [email protected].

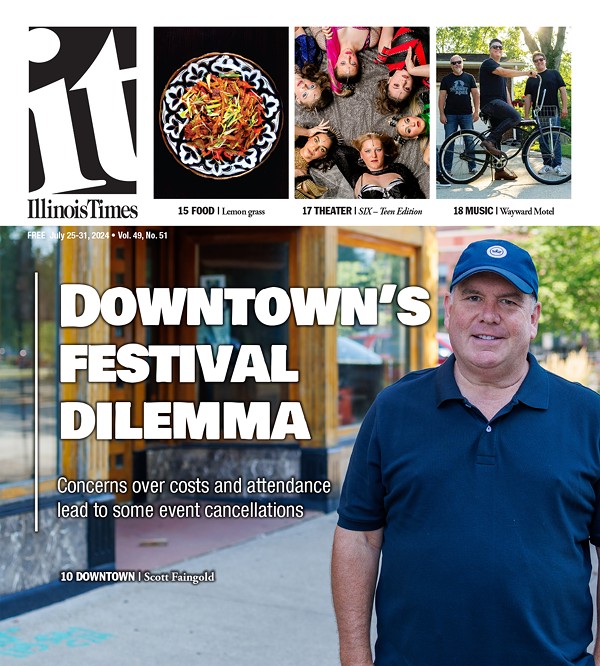

Illinois Times has provided readers with independent journalism for almost 50 years, from news and politics to arts and culture.

Your support will help cover the costs of editorial content published each week. Without local news organizations, we would be less informed about the issues that affect our community..

Got something to say?

Send a letter to the editor and we'll publish your feedback in print!