This story is a collaboration among Invisible Institute, IPM Newsroom and Illinois Times. Read the full investigation at illinoistimes.com.

Kyle Adkins was leaving his parents' house in Kincaid, a small village in Christian County, to pick up his young children from their mother's house on the night of May 8, 2021.

Kincaid Police Officer Sean Grayson pulled him over – but he wasn't sure why.

Grayson told Adkins there was a warrant out for his arrest and gave him a notice to appear in court, recommending felony drug charges against him. The case dragged on for two years before it was dropped, and a new investigation reveals the warrant – and other evidence Grayson said he had against Adkins – never existed. Body-camera footage shows Grayson admitting to the chief of police he had no evidence to recommend charges, but even after the footage surfaced in court, no other department or agency was notified.

Meanwhile, Adkins, who works as a mechanic, had to show up to court regularly for years, face questions about his reputation and deal with repercussions for his loved ones pulled into his criminal case. He said he even struggled to get formal visitation with his kids while the case was ongoing and said he's just now building a stronger relationship with his oldest, now 11.

Grayson, now 30, would go on to work at four other police departments across central Illinois, the last being the Sangamon County Sheriff's Office, where he would fatally shoot and kill Sonya Massey in her home in July 2024 after she called the police for help. Grayson shot three times at Massey, 36, an unarmed Black woman whose family had called police with concerns about her mental health, hitting her once in the head. He's since been charged with murdering her.

Police accountability and legal experts who reviewed multiple internal misconduct investigations involving Grayson, including Adkins' dropped criminal case, say Grayson's misconduct should have sounded alarm bells in law enforcement long before he applied to work at the Sangamon County Sheriff's Office.

"What happened to Sonya Massey is shining a glaring light on policy changes that need to be made if we are serious about holding the police accountable in Illinois," said Loren Jones, who directs criminal legal system reform efforts for Impact for Equity, a public interest law and policy center in Chicago.

Loopholes allow officers to move to other departments

Experts say that instances of dishonesty or questions about Grayson's credibility should have been reported to state authorities and documented for future background investigators. Such actions could have prevented the Sangamon County Sheriff's Office from hiring him in May 2023. The state's new discretionary decertification system, which makes it easier to strip officers of their ability to work in policing, went into effect in July 2022 but has been hampered by delays, according to a May 2024 report by Impact for Equity.

Gov. JB Pritzker, Attorney General Kwame Raoul and members of the Legislative Black Caucus were responsible for the passage of the SAFE-T Act, which reformed Illinois' police certification system for the first time in decades. Floor discussion was severely limited on the legislative package, which included provisions that cut off access to some records on police misconduct that were previously accessible.

But despite these reforms aimed at ridding the state of officers with significant misconduct, new reporting shows that little action was taken to stop Grayson from landing new jobs across central Illinois. Authorities in several police agencies that documented Grayson's misconduct internally did not report the problems to the state, as required, or to Grayson's future employers.

After Grayson left Kincaid and took a job with a different sheriff's office, a supervisor stated on a recording that he believed Grayson potentially lied on a report documenting his reasoning for a dangerous high-speed chase – but the department higher-ups never wrote that down in their report. Instead, they cleared him of misconduct and found he made a mistake, absolving the department of the requirement to report Grayson's dishonesty to the state.

Those same officials never interviewed a female detainee who said that Grayson had been inappropriate with her at the county jail and a local hospital, she said.

"Some agencies are more concerned about protecting the reputation of themselves and their officers than the safety of Illinois citizens," said Jones, the lawyer with Impact for Equity.

Officials have been circumspect about the next steps they intend to take, especially since Sangamon County Sheriff Jack Campbell announced his retirement on Aug. 9, effective Aug. 31. Officials with Pritzker's office and Illinois Association of Chiefs of Police, as well as members of the Legislative Black Caucus, ignored or declined requests for comment.

"I thought it was gonna ruin my life"

When Grayson stopped Adkins on the night of May 8, he didn't have his bodycam turned on during the stop, seemingly violating the Illinois Law Enforcement Officer-Worn Body Camera Act. (This would reappear as an issue in the Massey case, where the footage comes from the other responding officer.)

Some time after they arrived at the station, however, Grayson turned his bodycam on. The footage was obtained exclusively by Invisible Institute, IPM News and Illinois Times from the Christian County Circuit Clerk's office.

On the footage, Grayson claims he has video of informants making drug buys from Adkins, leading to a warrant being put out for his arrest. Grayson then tries to use those claims to convince Adkins to set up controlled buys with other supposed drug dealers in the area.

"Obviously, I got you on camera on two buys, OK?" he tells Adkins. "I'm not gonna lie. That's why you're here. That's why I was able to arrest you today. I have two informants that I busted for something, they did two buys off you. So today, I'll give you the same opportunity.

"If you want to work with us, we'll work with you," he continues. "We'll help you out as much as we can. We can never make promises, but this is what we do. Every time I bust somebody small, we try to get someone bigger."

In an interview with Invisible Institute, Adkins said he was incredulous.

"I just didn't understand why he was even, like, trying to charge me with this shit," Adkins said. "I can't believe it. He just kept saying, 'We know you're doing this,'" to which Adkins said he responded, "Well, obviously you don't, because I'm not doing that."

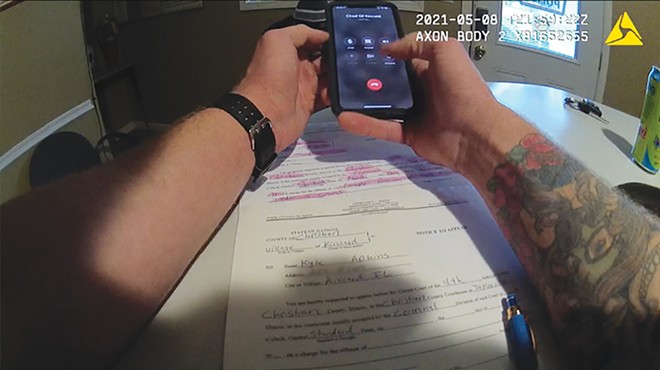

In the video, Grayson tells Adkins – who protests throughout that he doesn't know anyone he can buy meth off of – to consider it, then dials a contact labeled "Chief Of Kincaid" and asks the person on the other end how he should charge Adkins.

At the time, DJ Mathon was the chief of the Kincaid Police Department; he still holds that position today.

"Is it intent to deliver, just possession of meth, what do we put on that?" Grayson asks the person over the phone, while Adkins sits across the desk from him.

"Did he have anything on him?" the person responds.

"No," Grayson says.

The person audibly sighs over the phone. "On a Notice to Appear? I would just do intent to deliver," he says.

"Yeah, there was a baggie, but I wasn't gonna mess with field testing it," Grayson says. "I didn't really care that much."

"What was it?" the person asks.

"It was just, like, a baggie," Grayson responds. "But I didn't really care to field test it, to be honest with you."

During the video, Grayson can be seen Googling the Illinois Controlled Substances Act and the Methamphetamine Control and Community Protection Act while explaining the preliminary charges he's planning to bring against Adkins.

Adkins was released that day with a notice to appear in court. Because his car was impounded, Adkins had to walk home from the police station.

"I thought it was gonna ruin my life," said Adkins, now 29.

Felony charges of intent to deliver methamphetamines were filed in Christian County Circuit Court on May 17, 2021. State police certification records show that the next day, Grayson left the Kincaid Police Department.

On a form submitted to the Illinois Law Enforcement Training and Standards Board (ILETSB) on May 19, police chief Mathon wrote that Grayson had been "terminated," but that there was "no police misconduct related to [the] termination." In a later records request response letter, Mathon wrote that Grayson was terminated because he had declined to live within a 10-mile radius of the village.

Despite Grayson's departure from the Kincaid police department, that wouldn't be the end of the case against Adkins.

Police can often use strong-arm tactics in drug arrests

The day felony charges were filed against Adkins, Police Chief Mathon announced his campaign for Christian County sheriff.

"I plan to go directly after the source of illegal narcotics and go after the thieves that steal directly from Christian County," Mathon later said in a radio interview.

A few weeks later, on July 5, Mathon pulled over Brittney Myers, Adkins' girlfriend. In an interview with Invisible Institute, she said that while picking up a friend from an apartment building next to the police station, she saw Mathon watching her from his car.

"I backed up and he immediately jumped in his car and pulled behind me," she said. He told her it was for not wearing a seatbelt and because someone had made a noise complaint about her car exhaust. In response to a records request, Mathon said that no video of the stop exists.

She agreed to let him search her car. "I wasn't even concerned to let him look," she said, "because I didn't have anything." He found a plastic baggie containing cannabis flower that Myers said also previously contained THC crystals – a concentrated cannabis extract, and a legal substance to possess.

In his report, Mathon writes that he had pulled Myers over after seeing her and her passenger not wearing their seatbelts and that while searching her car with her consent, he "found a small baggie in the middle console with a green leafy substance and a white powder substance."

He writes that he let Myers go with citations for the seatbelts and her muffler, but afterwards "field tested the white substance and it field tested positive for methamphetamine."

Mathon arrested Myers on her mom's doorstep on charges of possession of methamphetamine. She said she spent the night in jail and lost both of her jobs after the department posted about her arrest on Facebook.

Throughout Myers' interaction with Mathon, he "kept asking if [Kyle Adkins] was selling, or if I could get somebody to set up or something," she said. "I kept telling him, 'No, I don't do that. I literally work in a day care.'"

After testing by a state lab showed the substance was cannabis, Christian County prosecutors dropped the charges four months later.

While field drug tests have become a tool of choice for police departments throughout the country, they are notoriously imprecise and often produce false positives that are "one of the largest known contributing factors to wrongful arrests and convictions," according to a recent report from the Quattrone Center for the Fair Administration of Justice at University of Pennsylvania.

Field tests for drugs can't be saved because they deteriorate, so it's often left up to the honor code of the officer whether the test came back positive for drugs, said Ralph Weisheit, an Illinois State University professor who studies crime, policing and their links with substance abuse in rural areas.

"In many cases, you can claim that there was a drug arrest when, in fact, drugs weren't there," Weisheit said.

These kinds of "strong-arm tactics" with potential confidential informants were something that Maybell Romero said she saw frequently as a prosecutor in rural Utah, before going on to teach law at Tulane University and study rural crime and prosecution.

"I have heard stories of people who have had nothing to do with purchasing or using or selling drugs, who've had their identity mistaken – or perhaps it's not a mistake. It's hard to know," she said. Some of these people, she continued, "have been enlisted as confidential informants because they're frightened of the police, or they're intimidated, and they don't know what else to do."

The warrant on Adkins never existed

Even after Myers' case was dismissed, Adkins would be called back into court over the next year. Then, on Sept. 1, 2022 – five days before the trial – then-State's Attorney Wes Poggenpohl filed a motion asking for more time.

Poggenpohl wrote, "One of the witnesses for this trial, Kincaid Chief of Police DJ Mathon, was reviewing his case file in preparation for trial. On Aug. 31, 2022, Chief Mathon called State's Attorney Poggenpohl to inform him that he had just located an audio video interview of the above-named defendant regarding this case. Chief Mathon was unaware of this interview until his review of the case file on Aug. 31, 2022."

Poggenpohl had inherited the case from former State's Attorney Michael Havera when Havera resigned to accept a new position with the state. Havera did not respond to an emailed request for comment.

The motion continues, "The officer who conducted this interview, Sean Grayson, departed the Kincaid Police Department sometime after this investigation without sending it to the State's Attorney's office." He wrote that he had not even had a chance to review the file when he wrote the motion. The video that had captured the conversation in which Grayson acknowledged to his supervisor that he had no evidence against Adkins was sent to Adkins's attorney, public defender Tiffany Senger, the next day.

Shortly thereafter, Poggenpohl lost his election bid, and said in an interview that he wasn't sure if he watched the video before turning the case over to the new Christian County State's Attorney, John McWard. He said the video surfaced just before the case was set to go to trial, after he asked Mathon to make sure all of the evidence had been turned in for the case.

In the next court filing after obtaining the video, Senger moved to throw out all of the evidence in the case as "illegally seized" because Grayson arrested Adkins "without a warrant or without other lawful justification."

She also added that the videos of Adkins selling drugs to informants never existed, according to her conversations with the state's attorney's office. Neither did the warrant for Adkins's arrest, she argued.

On Feb. 24, 2023, during a hearing over whether to suppress evidence based on the video, Christian County Judge Bradley Paisley dug into whether anything about Grayson's actions was legal.

The judge and attorneys all acknowledged that police can lie to a suspect during an interrogation. Where they differed was whether an officer can arrest somebody by lying about whether there is a warrant out for their arrest.

"That's quite a stretch," said Paisley, who previously served as Christian County State's Attorney, according to a transcript. "You tell somebody they've got a warrant for their arrest. That's a piece of paper signed by a judge saying arrest this guy for that offense. That's what (Grayson) told him. And it never existed."

State's Attorney McWard argued that Grayson's knowledge of the buys the informants allegedly made from Adkins – which Senger denied in court ever happened, and which no video existed for – was enough to have detained Adkins even without a warrant.

Judge Paisley said, "The primary question for me is... can you initiate the initial seizure based on the lie?" he said. "If he doesn't have the ability to lie to get that initial seizure, then the motion has to be granted."

During the next hearing, McWard moved to dismiss the charges without the judge ever ruling on Senger's motion.

When contacted in person at the Kincaid Police Department by Illinois Times, Mathon, who lost his bid for sheriff, repeatedly declined to comment.

Accountability mechanisms failed

Accountability measures broke down in more than one way in this case, police accountability and legal experts said.

When Grayson called the "Chief of Kincaid" and asked him for advice on what charges he should file against Adkins, Mathon – if he was the individual who answered the phone – should have advised him not to file charges without evidence said Jones, the attorney with Impact for Equity. But, based on the advice of the chief – who is the only supervisor in a department the size of Kincaid – Grayson issued Adkins a felony notice to appear, despite admitting that Adkins had nothing on him.

"His chief that was supervising him, and should have been that second line of defense against these issues happening, just reinforced his decision," said Loren Jones, of Impact for Equity.

Once the Christian County State's Attorney's Office became aware of the video and other evidentiary issues, it also had a responsibility to at least write a report documenting the issues in Adkins's case, said Rachel Moran, a law professor at University of St. Thomas in Minneapolis.

"If the prosecutor decided to dismiss the case because of Grayson's untruthfulness/misconduct, then they have an obligation to document that and disclose it in the future," she wrote in an email, pointing to prosecutors' obligations under decades-old Supreme Court precedent in cases such as Brady v. Maryland.

A request for comment to the Christian County State's Attorney's Office about why the case was dropped, and whether a report had been created, went unreturned.

However, the responsibility of the state's attorney in Christian County ends there, Moran, a former Illinois state appellate defender said, because Grayson moved to other jurisdictions. Ultimately, she said, "This is a huge gap in the Brady disclosure system and a major obstacle to accountability and fairness."

Law enforcement officials were also obligated to report the untruthfulness – once it was rediscovered in August 2022 – to ILETSB, which maintains an Officer Professional Conduct Database.

"Once law enforcement in Kincaid discovered the video and observed a likely violation of" policing standards, wrote Impact for Equity's Jones in an email, "they would have been required... to notify the ILETSB within seven days."

However, according to Attorney General Kwame Raoul, no law enforcement agency had ever submitted a report about Grayson until the Sangamon County Sheriff's Office made a report about Massey's killing.

Former Sangamon County Sheriff Jack Campbell has said that no red flags were raised during his agency's background check of Grayson. When asked by Illinois Times whether he knew of any misconduct by Grayson in Christian County, Campbell said he didn't.

Regardless, by the time the video was filed in court, Grayson had already been successively hired by three other departments.

Because submissions to the database are essentially left up to the honor code of police agencies, and largely secret from the public, Jones said the database has many gaps that leave officers like Grayson able to move around.

In the face of calls from Sonya Massey's family and activists for new legislation, leaders have declined to detail their thoughts about further reforms to the SAFE-T Act.

Senate Republican floor leader Steve McClure, a former Sangamon County prosecutor, criticized the Pritzker administration in an interview for the rushed passage of the SAFE-T Act, and called for a bipartisan legislative investigation "into what can be done to increase the transparency between departments."

In an interview with Illinois Times, Raoul said he hadn't read the Impact for Equity report describing reforms to the state's police decertification system as "stalled." He noted that portion of the SAFE-T Act was supported by police groups, unlike other aspects of the legislation.

It's unknown whether any failures of that system played a role in Massey's death, he said: "I just want to be cautious of pointing the finger at ILETSB."

After coming up with the police accountability reforms in the SAFE-T Act, Raoul said he and law enforcement groups agreed to "let them operate for a while in order to evaluate whether anything else needs to be done."

Raoul was reluctant to commit to supporting any specific legislative reforms connected to Massey's death unless the reforms would correct problems that have been documented throughout the state. However, he said, "An incident can expose a need." He added that state Sen. Doris Turner, D-Springfield, is looking into potential legislation.

Carlton Mayers II, an attorney and police reform consultant who worked with lawmakers on some of the original language of the SAFE-T Act, said ILETSB also still lacks administrative rules.

Those administrative rules would lay out not only the processes for discretionary decertification, but could also speak to things like what's required of a department's background investigation, which now only requires a check of the Officer Professional Conduct Database.

In a statement, a spokesperson hired by ILETSB pointed to its "multiple mandates to implement" for its delays.

"We are committed to leading this work thoughtfully and deliberately to ensure our law enforcement maintains the highest level of professional standards, and have made significant progress in building this new initiative from the ground up," the statement continued. "We have engaged a range of partners and studied best practices from across the country to ensure we get this right from day one."

The spokesperson wrote that the agency "anticipates" that the changes will be ready to roll out in the "fourth quarter of 2024."

Mayers said, "We're going to see more Sonya Masseys and more law enforcement agencies (claiming) they didn't know" about their reporting requirements until the administrative rules are in place and have teeth.

The missed red flags in Grayson's background – including Adkins' case in Kincaid – should have been caught by not only the state's safeguards, but also the final accountability mechanism: the Sangamon County Sheriff's Office's background investigation, said RaShall Brackney, an expert who reviewed the two-page report on Grayson.

"We have to become a nation of police chiefs or sheriffs or city managers or mayors that understand not everybody who applies to be a police officer should be a police officer, or deserves to be a police officer, because they applied," said Brackney, a former Pittsburgh police commander and chief of the Charlottesville, Virginia, police.

'Everyone believes a cop'

Adkins and Myers currently live in Mechanicsburg, a small Sangamon County village. They're both working – she as a store manager and he as a mechanic – and raising seven children together.

They left Kincaid, and rarely return to the village where their arrests led to lost jobs, loss of visitation with kids and broken relationships with family who believed they were guilty of the crimes they were accused of.

"It rubbed our names through the dirt," Myers said. "But everyone believes a cop," Adkins added.

This story was produced in collaboration between Invisible Institute, a nonprofit public accountability journalism organization based in Chicago; IPM Newsroom, a public media station based in Champaign; and Illinois Times. Sam Stecklow is a journalist and FOIA fellow with Invisible Institute. Farrah Anderson is an investigative reporting fellow with Invisible Institute and Illinois Public Media. Dean Olsen is a senior staff writer for Illinois Times.