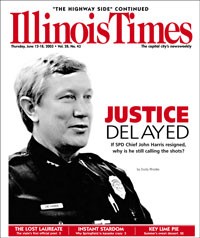

During the recent municipal elections, five men ran for the job of mayor. Four of them promised repeatedly that if elected they would immediately remove John Harris from his position as Springfield's Chief of Police.

Harris has been chief nearly eight years--much longer than any chief in recent history. He has survived his share of scandals, protests, and lawsuits, as well as a 90 percent no-confidence vote from his rank-and-file.

Then last fall, Harris was implicated in a controversy that some said was the last straw. The "Renatta Frazier case," as it's now known, involved a black female rookie officer subjected to countless media reports suggesting that she had failed to prevent the rape of another officer's daughter. These reports turned out to be totally false.

"We called for his resignation when the story first broke," says Alderman Frank Kunz. "I made no bones about it. Everybody knows where I stand. And it's not just an Eastside thing either. I work all over this city, and everywhere I go, everybody asks me: Why is Harris still here?"

Harris submitted his resignation with 30-days notice almost two months ago, just as Mayor Karen Hasara was leaving office and the new mayor, Tim Davlin, was coming in. Davlin has appointed an executive search committee to conduct a nationwide search to find a new police chief.

Meanwhile, though, he has asked Harris to remain on the job, and Harris appears content to do so. Sources inside the police department say Harris has not even started to pack his office or delegate responsibility. He continues to hold meetings, make plans, and call the shots. He is a lame duck with no sign of a limp.

Davlin was the one candidate who did not campaign on an explicit promise to fire Chief Harris. Instead, whenever he was asked about his plans for the SPD, he would answer with a curious aphorism that implied he had no use for Harris:

"A fish," Davlin would say, "rots from the head back."

* * *

There's a cliché pronounced whenever a new guy steps into a job vacated by someone with a sterling record: "Well, he's got big shoes to fill."

Nobody uttered that phrase when John Harris became Springfield's police chief back in 1995. Harris followed five years of scandal-plagued administrators: Harvey Davis, who became police chief in 1993 and was blamed for the disappearance of money, drugs and guns from SPD's evidence room; Kirk Robinson, chief for the preceding six months until he was accused of sexually harassing two female subordinates (who both eventually accepted out-of-court settlements); and Mike Walton, chief from 1987 to 1990, demoted back to sergeant after participating in a sex-and-blackmail scheme.

So there were no "big shoes" for Harris to fill. More like a pair of skanky flip-flops. To be counted as a success, all Harris really had to do was keep the squad cars running and his trousers zipped.

But just doing the bare minimum has never been Harris's style. He's been out of town recently and declined to be interviewed upon his return. By all accounts, though, he is a man of boundless energy and ambition who doesn't do anything halfway.

Only 44 years old when he applied to be Springfield's top cop, Harris had already accumulated enough professional, educational, and civic achievements to fill a seven-page resume. The one he's currently shopping around to prospective employers is undoubtedly twice as long and even more impressive.

Under Harris's leadership, Springfield Police Department won national recognition for its community policing policies as well as certification from the Commission on Accreditation for Law Enforcement Agencies (CALEA). Harris dazzled community leaders with the introduction of the Citizen Police Academy, the establishment of an Office of Community Relations at White Oaks Mall, the expansion of the popular Neighborhood Police Officer program, and the resumption of horseback patrols downtown.

He overhauled the entire department, "flattening" (that was his term) the top-heavy, highly-politicized structure through elimination of more than half of the appointed positions. He increased the frequency of SPD entrance and promotional exams, and revamped the internal affairs division, moving it blocks away from the main police station and staffing it with officers ranked lieutenant or above.

Harris avoided the particular pitfalls that tripped up his predecessors, but his tenure has not been without its scandals. Two years into his contract, he was faced with untangling what was, essentially, a bar fight involving several off-duty SPD officers and one unlucky civilian. Known as "the Office Tavern incident," the scuffle led to several trials, plus various degrees of punishment for the officers, and provided countless hours of fodder for talk radio.

A few years later, Andy Sallenger, a young unarmed mentally ill man, died after being subdued and hog-tied by three SPD officers; his family's lawsuit against SPD is currently pending in federal court. And finally, there was the Renatta Frazier debacle.

Besides these scandals, Harris was plagued with behind-the-scenes grumbling from his troops almost from the get-go, which is standard procedure at SPD.

"You've got two strikes against you when you walk in the front door--the union and the political atmosphere," says Sangamon County Sheriff Neil Williamson, who spent 21 years working at SPD. "Plus, he was an outsider, so he was automatically considered suspicious. He had an uphill battle."

While Harris spent his first few months formulating his reorganization plan, the police union fretted that he would fail to replace the most scandal-tarnished brass (and, indeed, Harris demoted only two members of upper-management). Labor relations went from bad to worse: The rank-and-file worked 18 months without a contract and in 1998 won $800,000 in back pay. But that contract has since expired; they've now been working without a contract for more than two years. When union members complained about "manning" (the number of patrol officers on the street), claiming some beats were left uncovered, Harris responded by re-drawing the beat map, making each beat bigger.

Morale ebbed so low that the confidence vote called by the Policemen's Benevolent and Protective Association No. 5 in 1998 showed nine out of 10 officers had no confidence in Harris.

* * *

It was another no-confidence vote that set Harris on the path that eventually brought him to Springfield.

Harris began his law enforcement career in 1974 as a patrolman with the Tucson Police Department--an agency with close to 800 officers supported by approximately 300 civilian employees and another 300 or so volunteers. According to his resume, he was assigned to the Special Weapons and Tactics team from 1978 through 1988, achieving the rank of lieutenant before moving to the hostage negotiations unit. Over the next five years, Harris was promoted through the ranks to captain. His wife, Barbara, who was also a TPD officer, achieved the rank of sergeant.

In 1992, TPD's long-time chief Peter Ronstadt (Linda's brother) announced his retirement, and the city chose to hire from within. Harris was one of six finalists, but the job ultimately went to Elaine Hedtke. She soon promoted Harris to assistant chief.

But the rank-and-file were immediately disgruntled with Hedtke, says Joe Burchell, a veteran city hall reporter at the Arizona Daily Star. "They thought she was anatomically challenged," he recalls.

When Hedtke suspended without pay a pair of cops accused of roughing up a teenager, the officers saw their chance to oust her. The Fraternal Order of Police (of which Harris had been a member) held two rallies against Hedtke. Tucson's city council, meanwhile, held a press conference to express support of Hedtke. Some council members encouraged the chief to take whatever steps necessary to regain control of her department.

"They said they believed some of her command staff was trying to undermine her, at least partially because she was a woman and because some of them want[ed] her job," according to a 1992 article in the Arizona Daily Star.

Apparently, some council members told the press that Captain John Harris was fomenting the unrest.

"City Council sources last week named Harris as one of three top commanders who was undermining Hedtke's control of the department and provoking the outburst by officers in the department," the Daily Star reported. "Those assertions were disputed repeatedly by Hedtke and her commander."

Hedtke demoted Harris back to his rank of captain. The newspaper reported that Harris was demoted for "blatant insubordination" after failing to reprimand another captain, Linda Burkett, who publicly asked for the chief to resign.

But Hedtke now says there was a bit more to it than that. "It was a captain accusing me publicly of being a liar," she says. "In discussion, I had determined that John had been aware of what Captain Burkett felt and intended to say, and he took no steps to advise me or deal with it in a way that was less difficult, less disruptive to the organization. I felt that that constituted a lack of leadership on his part as an assistant chief. And therefore I demoted him back to captain."

The following week, the FOP released a letter listing 14 complaints against Hedtke, including the fact that she had "demoted and publicly humiliated" John Harris.

Eventually, both Harris and Hedtke left the TPD--Hedtke for another job with the city, and Harris to "retire" to a small town in Missouri, apparently to work as director of Trans-Soviet Outfitters, leading bear hunts in Siberia. When the local police department started looking for a chief, Harris took the job.

Kirk Powell, editor and publisher of the Pleasant Hill Times, has fond memories of Harris's two-year tenure as chief over a force of eight officers in a town of 4,000. "He just had a great approach to it. He seemed to be able to get the job done while rustling the fewest feathers as possible," Powell says.

"For example, we had a place in town that was a pool hall and bar selling beer to minors pretty regularly. Instead of making a big deal out of it, Harris would just pop in two or three times a week and have a Pepsi. He told me, 'They never really know when I'm coming in!' And that fixed the problem.

"He was probably one of the best small-town law people I've ever seen," Powell says. "He had far superior management skills. We were just lucky to have him as long as we did. I think we're still enjoying the benefits of that. He set a tone and a pattern for the police department here that still continues."

* * *

Harris was one of 58 applicants for the job of chief over the Springfield Police Department. When he was selected, the media described him as an assistant chief from Tucson, not mentioning that he had held that post less than a year. Alderman Kunz doubts the investigation into Harris's background was very thorough.

"He fed us a line of horse s---and we all fell for it," Kunz says.

Harris was unanimously approved by the City Council on October 17, 1995, and began work on October 23 with a 6:30 a.m. meeting with his command staff. On January 5, 1996, he signed a four-year contract with the city. His salary was $69,000 per year.

Harris seemed to want to get the community involved in the resurrection of the police department. He had officers and citizens meet with him and Mayor Hasara to come up with a "mission statement" for the SPD--that the police will "work in partnership with the community to promote open communication, education, cooperation, and fair and equal treatment to improve the quality of life, promote unity, encourage respect and make Springfield a safe community." He fostered a personal connection between the community and his agency when he got an auto parts store, an American Legion post, and a church to sponsor bullet-proof vests for SPD officers.

Sheriff Williamson recognized that Harris had talent as a politician. "He always said he wasn't a politician, but he's a bigger politician than I am, and I'm an elected official," Williamson says.

But some of the innovations that won Harris praise from the public had the opposite effect inside the agency. For example, the popular Neighborhood Police Officer program that assigned officers to certain neighborhoods and schools was a sore spot with the union, which complained that too many officers were assigned to special units.

Other problems he simply created for himself. One of his first official moves was the hiring of Mark Faull as his assistant at a salary of $54,500 per year. Faull had been a police officer in Tucson, but left the force to earn his law degree. He had followed Harris to Missouri, where he worked as county attorney. In Springfield, Faull signed on as a civilian employee, yet within a few months Harris arranged for Faull to be sworn in as a police officer with the right to carry a gun.

The union pointed to Faull in the summer of '97 to force Harris to withdraw his proposal for "lateral entry"--hiring officers from other agencies. Harris had pitched the idea as a way to add minority officers to the ranks, but the union saw lateral entry as a blank check for Harris to bring in his buddies, like Faull, from Arizona to leap-frog over local officers trying to work their way up the ladder.

As a compromise, Harris joined union leaders in a proposal to increase the frequency of the police department's hiring test from once every three years to once annually, with promotion exams given every two years. But the controversy had focused attention on Faull's gun-carrying privileges, and an alderman requested a legal opinion. Then-corporation counsel Bob Rogers ruled that Faull never got proper approval to carry a gun in Springfield.

Harris's battles with the union continued. In September 1997, union trustee Bob Vose testified before the City Council's public affairs and safety committee that SPD left two or more beats unmanned more than 10 percent of the time, especially during the first shift of the day (7 a.m. to 3 p.m.). There were occasions when as few as 10 officers were on the streets, according to schedules produced by Vose. This led Harris to re-draw the beat map a few months later. Instead of 14 small beats, the city was now divided into eight bigger beats. Vose called the chief's tactic "smoke and mirrors."

The following year, Harris again angered his officers just as they were preparing for the first promotion exam in several years. When the list of books to study for the exam was announced, at least two officers admitted they had an unfair advantage because they had already been reading these books--thanks to Harris's suggestion. The test had to be postponed.

As Harris's first contract renewal date approached, the union took a formal confidence vote. Ninety percent of PBPA members voted; 89 percent of those said they had no confidence in Harris's ability to lead the department.

By a 9-1 vote (Alderman Cecilia Tumulty voted "present,") the council renewed his contract anyway.

* * *

Of course, the toughest tests faced by any police chief are the pop quizzes--the "incidents" that crop up in the middle of the night, typically, when officers find themselves having to make judgment calls in the dark. The public will focus first on the patrol officers for their actions, but scrutiny soon shifts to the chief and his handling of these events.

Harris's first big test was the Office Tavern incident--more than three years into his tenure here. Although unanswered questions may linger (mainly because everybody involved had been drinking), this incident has been probed, investigated, and litigated multiple times.

Three trials resulted in no finding of fault against the SPD. At the request of Mayor Hasara, the Illinois State Police reviewed the department's response to the incident and found "a significant breakdown of communication between line officers and upper command personnel." Among the recommendations listed by the state police was one that would factor into a later scandal-- "Police Report Command Review." The state police recommended that: "Written policy should be implemented to define how and when police command [high ranking officers] are to review written police reports. Reviews should be required to ensure that upper command review the written reports of specified incidents. . . . "

In other words, the brass ought to read the reports on any high-profile incident.

Had this recommendation been followed, the Renatta Frazier case should have never happened.

Frazier was a rookie cop, dispatched to investigate a call from a female who said men were banging on her apartment door. When Frazier arrived at the apartment, she saw no one. When she had dispatch phone the complainant, the call was answered by voice mail. Frazier cleared the call and left. The next morning, the girl reported that she had been raped.

This case was made more newsworthy by the fact that the rape victim was the daughter of a police officer. Within weeks, word that Frazier was being investigated "for failure to prevent the rape of a fellow officer's daughter" was leaked to the daily newspaper and rebroadcast repeatedly by the electronic media.

This scenario was false, as anyone who read the incident report knew. The rape had occurred before the girl ever called police, and before Frazier ever arrived at the scene. But the false reports continued for almost a year, until a story in this paper revealed the truth.

Harris has never answered the question of when he knew the truth. But the inevitable conclusion that he either knew and did nothing to correct the situation or was oblivious to what was going on in his own agency was so troubling that several aldermen and civic groups started calling for his resignation.

It came, supposedly, on the day Mayor Hasara left office. Now a matter of debate, this letter has not been released even to City Council members. There is speculation that the letter mentions retirement as well as resignation, and that Harris bought enough military time to be eligible to receive a pension.

Harris has made no secret of his desire to remain in Springfield, and he has several reasons to want to do so. He has a high-school aged daughter who would love to graduate with her friends. And his wife, Barbara Harris, has a contract with the Illinois State Police as a public service administrator working full-time at a pay rate of $45 an hour, according to State Police spokesman Master Sergeant Rick Hector. Her contract expires in July, and "is under review at this time," Hector says.

For a while, the rumor mill cranked out suggestions that Harris might stay on with the city in some other capacity (director of hometown security, for example), but people close to the mayor say that simply won't happen.

"I haven't seen any application or resume from him applying for any other position," says Letitia Dewith-Anderson, Davlin's chief of staff.

Alderman Chuck Redpath, who was a major contributor to Davlin's campaign, says he hopes the mayor doesn't consider Harris for any position.

"I think Harris is a lightning rod and things that happened in the police department will overshadow any position he could have," Redpath says. "I just don't think he'd fit."

Alderman Kunz is characteristically blunt: "I will not be happy if Harris stays on in any capacity," he says. "If he does, I would imagine that Tim would lose a lot of support. John Harris is going to cost us a bunch of money. The Renatta Frazier case is his fault and nobody else's."