The conference on "The Hope and Promise of Co-liberation Work" began with a celebration on Friday, Feb. 17. It was followed by two days of lectures, panel discussions and breakout sessions that together showed how far the Springfield medical community has come on the road to racial and ethnic inclusion, diversity and equity. And how far it has to go.

Dr. Jerry Kruse, dean and provost of SIU School of Medicine, announced at the opening session that Dr. Wendi Wills El-Amin, who is associate dean for SIU's Office for Equity, Diversity and Inclusion, and professor of family and community medicine, has been promoted to the rank of full professor. A video tribute to El-Amin featured dozens of students and coworkers, many of them Black, some Asian, each giving testimony to how she has helped them negotiate the difficulties of medical school and career. In her speech accepting the promotion, El-Amin said it feels like "freedom," at least for a moment. Out of 40,213 full professors of medicine in the United States, only 374 are black women. SIU School of Medicine has been seriously engaged in systemic antiracism efforts for about eight years now. Dr. Kemia Sarraf, a codirector of the conference, commented, "The school of medicine became unstuck, like it had needed to be unstuck for many years."

During a panel discussion on Saturday, El-Amin said leading the EDI office is "the hardest job I have ever had. I have to walk a fine line. It is exhausting." Others on the panel of powerful women with years of experience in antiracism work spoke about the tension that accompanies their jobs, and the need for self-care. Dr. Sheila Caldwell, chief diversity officer for the Southern Illinois University system, spoke of sometimes feeling "only and lonely," then added, "You may be the only one in the room who recognizes what harm is being done." An audience member said some powerful men in medicine don't even try to follow established diversity and inclusion protocols. A panelist replied, "Without accountability and enforcement, that's why we're still where we are. We need hearts and minds, but also policies and laws."

This was the annual Kenniebrew lecture, conference and forum, sponsored by SIU School of Medicine, Memorial Health and HSHS St. John's Hospital to shed light on health disparities. The event is named for Dr. Alonzo Kenniebrew, a physician who opened a surgical hospital in Jacksonville in 1909, the first African American in the U.S. to do so. Kenniebrew founded the hospital because he could not obtain medical privileges at area hospitals.

Conference sessions included both corporate systemic efforts to address racism in health care, and training in personal skills to deal with difficult everyday conversations. The latter was led by Kelly Hurst, a Ph.D. candidate and former elementary school teacher who now instructs medical students. "Be an active bystander," she urges those who might otherwise be inclined to keep quiet when they hear a racist joke or a misogynist comment. "State you are uncomfortable with what was just said. Or you can say, 'That's unacceptable.' Ask for clarification or invite discussion." More than once, attendees said the conference was "preaching to the choir," implying that others need this education more than they do. "Yes," Hurst would reply, "but this choir needs to go to rehearsal." Nobody is ever fully ready to perform.

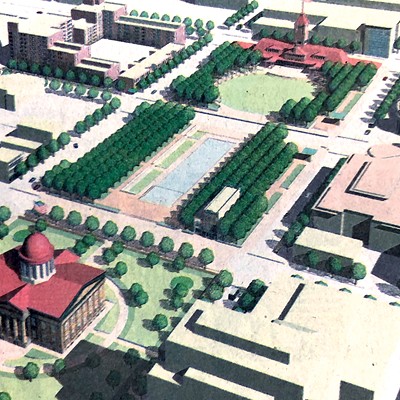

Three physicians who work in SIU's Office of Equity, Diversity and Inclusion – Vidhya Prakash, Chris Smyre and Shreepada Tripathy – led their breakout room in an exercise about getting health care to where it's needed most. With detailed mapping from electronic health records, they identified the two Springfield census tracts where Type 2 diabetes is the worst. Then the group tried to help these doctors figure out how to get these people the medical care they need. "They may have a car but no money for gas," we were told. One idea was to take doctors to them. Then it turns out SIU has already set up a Health DEPOTS program that takes health screening and monitoring to churches, schools and other community centers in neighborhoods rife with diabetes.

"Co-liberation" in the conference title was amplified with a quotation from Lilla Watson, an Australian activist and artist: "If you have come here to help me, you are wasting your time. But if you have come because your liberation is bound up in mine, then let us work together." Leaders emphasized that everybody is harmed by systems of oppression, and when some are unbound, everybody is less bound.

Also, there are different levels of joining the struggle. "Standing in solidarity" and being an "ally" are OK, but they don't follow a strategy. Being a "co-conspirator" is a stronger commitment, but it implies following a Black leader. Being a "co-liberator" is the strongest commitment "because it gives everybody agency to carry their own water." Co-liberators can say, "I will join in a legacy of non-Black antiracists and abolitionists who challenged racist structure in their own families, in their careers and in their communities."

Fletcher Farrar is editor of Illinois Times.