June 11, 2008, was my daughter's 10th birthday, but instead of frosting a cake, I was filling sandbags in Cedar Rapids, Iowa, where we lived. The rain seemed to fall without end that spring, and the Cedar River was threatening to overflow its banks. I was the director of marketing for the National Czech & Slovak Museum & Library, which was situated on the river. The day was spent evacuating artifacts and books, moving items up on tables, and putting a wall of sandbags around our collections facility. We were all working swiftly, but remained cheerful, feeling sure that our efforts would be enough – maybe even more than what the river would demand of us. By 3 p.m., water started coming up from the storm sewers and filling in low spots downtown. The city evacuated our little ethnic neighborhoods of Czech Village and New Bohemia and we went home to watch and wait.

On Friday, June 13, the Cedar River crested at just over 32 feet, which was nearly 20 feet above flood level. It wasn't a 100-year flood, it was a 500-year flood. More than 10 square miles of our city was drowned. Some 1,400 jobs would be lost and 45 day cares closed. Losses reached $5.4 billion. How would our city recover? It seemed nearly impossible.

Fast-forward 16 years and it is clear that Cedar Rapids has harnessed the opportunity inherent in a crisis. Empty and underutilized spaces have been repurposed and rejuvenated. An urban bike trail connects an eclectic mix of apartments, condos, cafes, restaurants, shops, entertainment venues and cultural institutions. New Bo City Market offers an indoor shopping hub that is hip and vibrant year-round, accompanied by frequent outdoor events, ranging from music concerts to yoga.

The ethnic neighborhoods of Czech Village and New Bohemia have leaned into their history and strengthened their brand, curating memorable visitor experiences and deepening residents' sense of place. Museums and a beautifully reimagined public library serve as important cultural anchors. An innovative educational model, Iowa Big, brings high school students from all over the school district and puts them to work on projects that embed the students in their downtown. It is next to the business accelerator, NewBoCo. There is real energy in the downtown. A sense of vibrancy that had been fading for decades before the flood.

What made this transformation possible? Leadership, unity of vision, talented city planners and community co-creation. First, Cedar Rapids looked outside of itself to study benchmark cities with successful neighborhood planning initiatives worth emulating. Second, it deeply involved the community in every step of the planning process. Third, it secured strong local, state and federal support to implement the plan. The vision was compelling and bold – make our city more resilient to future flooding while simultaneously attracting a younger workforce. Local developers stepped up. Private-public partnerships flourished. And all you had to do was look around and see that people from every sector of the city were seizing the day.

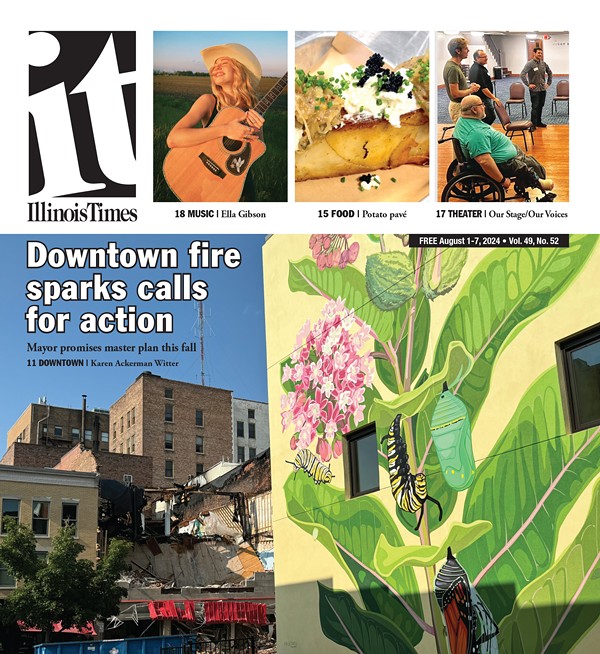

The evening of the June 19 fire, I spoke to a news reporter, who asked me if I was worried about the future of Adams Street. I said in the short term, yes, but not in the long term, because I know the people in this neighborhood, and I believe we really can come back better. The flood in Iowa taught me that was possible.

Springfield's downtown may not have been consumed by an angry river, but it certainly has endured its share of disasters. Many of these aren't painfully visible, like the aftermath of a flood, or fire, which perhaps makes them easier to ignore and harder to solve.

We've lost 5,500 government jobs since 2004. Two governors hacked away at our historic sites, state parks and cultural institutions to balance the budget. The Illinois State Museum, which used to attract more than 200,000 visitors per year at its primary location downtown, was closed for more than nine months. Key personnel were fired. Given the extraordinary challenges of recovering from such a disruption, I'm not sure a flood or a fire would have been worse for its future. All of this, and then a pandemic, has left us with a downtown that often feels forgotten. If, like our building on Adams Street, we took all the vacant buildings downtown and tore away the facades to be faced with their emptiness, how might we be compelled to act?

Becoming the city we all dream of depends on a unified vision for our ambitious plans – Springfield's Rail Improvements Project, CAP 1908, the Downtown and Medical District Master Plan, and The Next 10 – and the audacity to see them through.

This fire, while devastating, is an important reminder of what is at stake. We cannot predict or prevent all disasters – natural, economic, or otherwise – but we can control how we grow from them. Let this be the moment that strengthens our resolve to become a city that inspires, connects and uplifts us all.

Leah Wilson is executive director of Kidzeum of Health and Science at 412 E. Adams St. in Springfield.