Makiya Burton is a Springfield mother who worries that her children are not learning to read.

"My children have a struggle with reading. I have a family history of having trouble with reading as well," Burton said. "One of my kids is getting better at reading. And one of them is still down there struggling. I just feel all of our kids deserve to learn how to read for their future success."

Burton's school-age children, who are 7 and 9, are not alone.

In fact, three out of four Springfield Public Schools District 186 fourth graders are not proficient in reading and writing, according to the Illinois State Board of Education. The 2023 Illinois Report Card, released last fall, is an annual report that ISBE prepares to show how schools and districts across the state are performing.

The union representing teachers, the Springfield Education Association, blames administrators for saddling their members with a curriculum that has proven ineffective.

It's a charge for which administrators have a practiced response: "Our teachers don't teach curriculum, they teach children." Among the administrators who shared this response was Assistant Principal Simon Wilson of Harvard Park Elementary School.

At issue is a method of instruction developed by Columbia University professor Lucy Calkins, which is used in Springfield classrooms and about 25% of the nation's elementary schools. Many others nationwide use curriculums influenced by Units of Study, Calkins' "balanced literacy" curriculum that emphasizes learning words through context rather than by sounding out words.

In a typical Calkins classroom, instructors read aloud from children's literature; students then choose books which fit their interests and ability. The focus is on stories – theme, character, plot – less on sounding out words.

A controversial curriculum

In recent years, the curriculum has come under fire nationally from both parents and educators who advocate for the "science of reading." They cite 50 years of research that shows phonics – sound it out exercises – is the most effective way to teach reading, along with books that develop vocabulary and depth.

Ben McKinney, a third-grade teacher at Fairview Elementary School, was blunt in his criticism of the district's reading curriculum.

"I'm pretty sure it is garbage," he said. "I'm trying to be nice about it. It wasn't well-written in the first place, and it left out a lot of things that our district specifically needs, such as an early focus on phonics. That was a big piece that it didn't have. Four or five years after we started using it, they came out with a phonics unit, but by that time we'd already had four or five years' worth of kids go through without as much explicit phonics as we think they needed."

The appeal of the Calkins curriculum often has more to do with educator enjoyment than pupil learning, said Anne Brewster, executive director of the Dyslexia Center of Springfield.

"The whole-language approach (that Calkins advocates) makes an erroneous assumption that reading is acquired sort of the same way oral language is acquired, where with enough exposure, you just will naturally become a reader," Brewster said. "You fairly naturally learn how to speak and how to understand oral language, because we've been doing that for so long as a species that our brains have evolved these language centers that are primed when we're born to acquire language.

"And so there was an assumption made that that must be true of reading and writing as well. This assumption dates back to the 1960s – and that turns out to be false. But a lot of instructional methods were built up around this idea, because teaching phonics is very boring," she said.

Ever since the book Why Johnny Can't Read was published in 1954, the education community has been engaging in an ongoing tug-of-war between those advocating for a phonics-based curriculum and those embracing memorization or "sight words."

But the Calkins curriculum has poured gasoline onto an already blazing fire.

The popular podcast "Sold a Story" and the documentary Right to Read condemn this teaching approach. In response, Calkins has recently added more phonics instruction into her curriculum.

"It's not like Springfield is doing this worse than everybody," said Jessica Handy, executive director for Stand for Children Illinois. The grassroots advocacy group, based in Springfield, works to pass education reforms, and literacy efforts are one of the organization's focus areas.

"Many people have been doing this poorly, and there's somewhat of a collective understanding that we need to be more thoughtful about how we're teaching kids to read," she said. "You want reading to expose them to other cultures and ideas, but if they can't pull the words off the page, they can't do any of that."

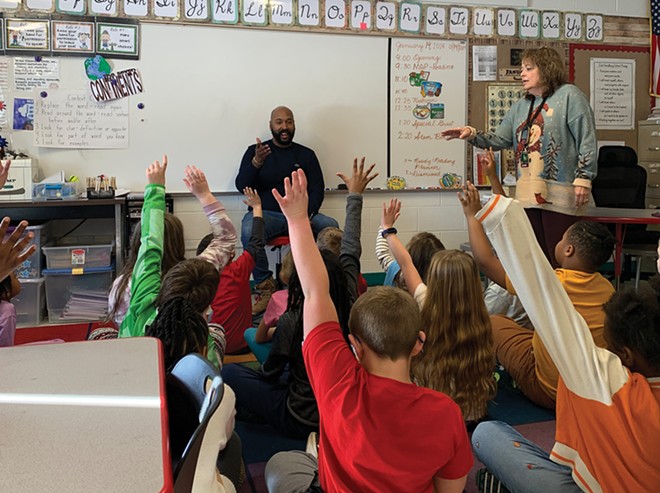

Indeed, Springfield Public Schools is doing many things right. Reading specialists give individual attention to some students who struggle. A reinvigorated Real Men Read program is filling District 186 schools with male role models who read books to youngsters. Programs such as Compass for Kids have partnered with the public schools to provide summertime and after-school mentoring in reading and other subjects.

But the district's adherence to the Calkins curriculum remains an albatross around the neck when it comes to reading proficiency. District 186 – and other Illinois school districts – are now moving away from this teaching approach.

"We're on the journey for a new curriculum resource to support our teaching practices," said Dr. Nicole Nash Moody, assistant superintendent of teaching for District 186. "I will tell you that this transformation, or what the field calls 'shifts in reading,' has been fundamental to us as leaders of literacy as well as teachers in (that the methods) which we thought children were learning how to read were not working for all children.

"And that's difficult for me, as an educator, to say out of my mouth. I thought that what I was doing (was beneficial). I went to school and went to classes and did all of these things that I thought would be helpful to my students. I still had students who were not reading. And I, as a teacher, didn't really understand why," she said.

Stand for Children successfully lobbied the General Assembly last year to have legislators pass a measure geared toward guiding school districts away from the Calkins curriculum.

"It required the State Board of Education to create a comprehensive literacy plan by January of 2024," Handy said.

But the plan developed by the state board is only advisory – no mandates are placed on any local school districts to adopt a particular curriculum.

"We couldn't pass a mandate. We tried the year before to do something that would have required ISBE to create a curriculum list, sort of like Colorado does," Handy said. "But it was universally opposed by almost everybody. It became really clear that we weren't going to be able to get strong mandates, but what we wanted to do was see the State Board of Education taking a leadership role in raising Illinois literacy rates."

Handy said the ISBE document favors phonics instruction as well as oral language development, fluent expressive reading, vocabulary, comprehension and writing.

District 186 is in the process of moving away from the Calkins method. In fact, the school board is expected to vote in March on a new reading curriculum.

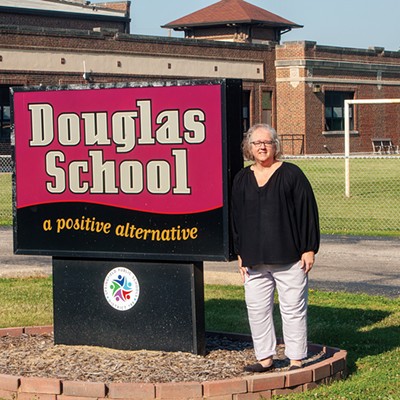

Learning a new way to teach reading

Just how the district finds itself on the cusp of change is a story of the politics of pressure. It began with the SEA creating a task force to address the literacy problem in the district.

"The task force just had to exist to put the pressure on the school district to do what they should be doing," SEA President Aaron Graves said. "Through some collective and some awkward conversations, the school district has taken the lead to explore other curriculums. The district is doing a noble job in both the elementary and the middle school rounds, where they've assembled teams of very diverse educators across grade levels and across all four corners of town to really look carefully at five or six different curriculums," he said.

"The other thing they are doing is they are starting the process of professionally developing all of the teachers who teach reading as to what the research actually says. We missed that in our teacher prep programs," Graves said.

College teacher preparatory programs have largely embraced the Calkins approach during the past several decades.

"It's a really delicate topic to talk about without making teachers feel criticized," Kenni Alden, co-founder of the California-based Right to Read project, told Illinois Times. "It's not the teachers' fault. They don't choose their curriculum and also, they're reliant on what they've been taught in their teacher training programs.

"They were taught a literacy philosophy. This belief system has a mystique to it. It feels magical. It feels warm. It feels good to adults. It feels particularly good to privileged adults who already know how to read," she said.

Rather than pushing youngsters through the tedious process of sounding out syllables, the Calkins approach contends that learning to read comes naturally to children, in part through exposure to quality literature, Alden said.

While an appealing notion, it has proven to be an erroneous approach, she said. Alden said this methodology has been particularly devastating to children growing up in poverty.

"Families with resources will remediate, whatever's happening or not happening in school," she said. "They may hire tutors. And they are more likely to have books to read to their children. But kids in lower (socio-economic strata) schools are relying on school to teach them to read. That's the only way they're going to learn how to read."

"Enormous disparities in resources"

Springfield mom Burton added, "I'm a good parent even though I don't read with my kids every day. I feel like it takes a community to teach children how to read. It is not all on parents. I feel like it's a parent and a teacher's job to teach children how to read. I'm not an expert on reading. I count on the school to teach my children to read."

Her children attend Matheny-Withrow Elementary School, where 74% of students are from racial minorities and 76% are from economically disadvantaged backgrounds.

While 76% of all District 186 fourth graders lack proficiency in reading and writing, the story for Black fourth graders in the district is even worse, with 86% lacking proficiency.

"Sometimes people will try to say children growing up in poverty are just naturally less likely to learn to read. That's a load of crap," Alden said. She added it is about how a child is taught.

However, within Springfield there is "enormous disparity in resources devoted to students," Graves said.

Twelve years ago, in a round of cost-cutting moves, District 186 eliminated librarian positions in all of its elementary schools. For many schools, such as Harvard Park Elementary School, this meant the school would no longer have a library.

Some schools, disproportionately in the city's more affluent neighborhoods, have maintained their libraries through fundraisers and having parent volunteers staff them, Graves said.

"I'm aware that teachers try to meet our students where they are and move them up," Assistant Principal Simon Wilson said. "Using the resources and tools that we have available from the district and following their protocols, we've made some gains. That's been a celebration for us here at Harvard Park in the area of literacy, but we still have got a long way to go."

While progress has been made, 97% of fourth graders in the high-poverty, majority Black school are not proficient in reading and writing, according to the Illinois State Board of Education.

"I'm a huge advocate of a school library," Wilson said. "I think it's the center of information. But we don't have a school library. We don't have a school librarian. That's a struggle that is real. Yes, we do have classroom libraries. It seems like that's been the new trend. But I think libraries are crucial in schools, especially since in the community libraries have been shut down," he said.

"I'm a product of Springfield as well; I remember when there was a library on each side of town. There no longer is anymore," Wilson said.

Between 2005 and 2010, the city of Springfield closed all three of its branch libraries, citing financial considerations. Educators say children's lack of access to books is a factor in why so many are not learning to read well.

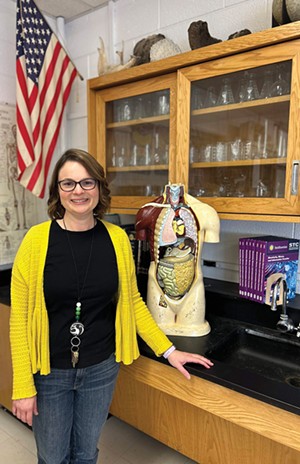

There is a need for urgent change in the way reading is taught in Springfield schools, said Melissa Hostetter, a teacher at Franklin Middle School. While she currently teaches seventh-grade science, she previously taught middle school language arts and has also taught at the elementary level.

"I don't think a lot of parents even realize the crisis their kids are in," she said. "We don't want a parent to feel like their child can never get turned around. But we have to be sincere about the gaps in a child's education. If it's not turned around by grades two or three, the odds of getting there become less and less every year. It's scientific. We talk about test scores, but these kids leave our school district and become adults.

"So, this is about having a literate society, a literate community of people who can write in a way that they can advocate for themselves. They can read a job application. They can read their mail. They can read a menu. They can just live in society and be able to read everything that they come across," Hostetter said. "I don't really care so much about test scores. I care about what is going to happen to these kids when they're adults."

Scott Reeder, a staff writer for Illinois Times, can be reached at [email protected].