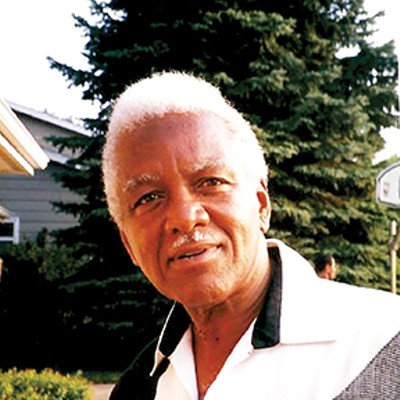

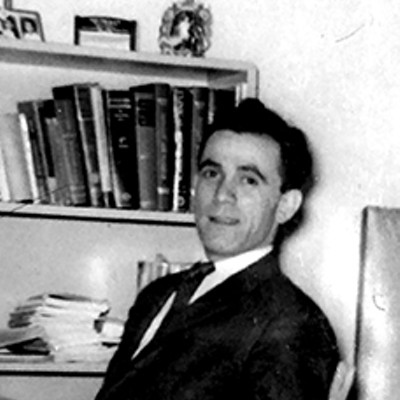

Archie Lawrence didn't thunder.

As president of the Springfield chapter of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People, Lawrence was soft-spoken but determin ed and deliberate in thought and manner.

"He didn't have to yell or be verbose," says Gail Simpson, a former Springfield alderman who represented Ward 2. "He knew what he had to do, he knew what he had to say and he said it in a manner that was thought provoking. And he made his point."

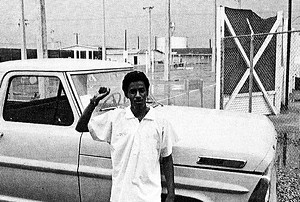

Consider photographs taken when Lawrence was in high school and college. More than once, he posed, fist raised, in the black power salute. Frank McNeil, former Springfield alderman and a plaintiff in a voting rights lawsuit that led to today's aldermanic form of government, says it took courage, back then, to raise a fist in public: He confesses that he was camera shy during his college days, which wasn't unusual for black activists who feared consequences from would-be employers or the Federal Bureau of Investigation. In those days, he said, speaking out could be dangerous.

"You would think that he's meek and mild mannered, but he had a ferocity about him," McNeil said. "He believed in justice and civil rights, and he fought all his life for it."

Born and raised in East St. Louis, Lawrence had a dozen siblings. "We used to call him 'Professor,'" says Terry Lawrence, an older brother who owns a men's clothing store in Springfield. "He always had books and stuff – he was real smart."

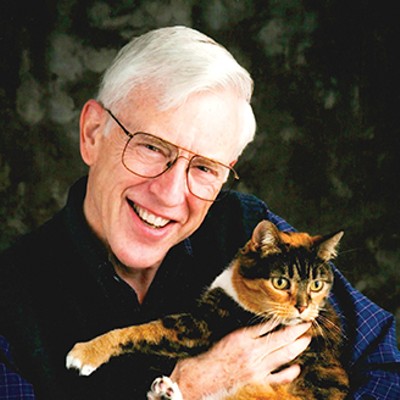

Raised by a stay-at-home mother and a father who had several jobs, including a position as a school truant officer, Lawrence, who'd protested the Vietnam War during college, got drafted after graduating from Southern Illinois University. He left for boot camp on his birthday in 1971 and was sent overseas, where he worked as a clerk and was spared combat. Ernestine Lawrence, his widow, says he wrote letters to her almost every day. Their marriage lasted 43 years until he succumbed to cancer.

After discharge, Lawrence got a degree from St. Louis University Law School, then moved to Springfield, where he became a lawyer for the Internal Revenue Service, then for the state attorney general's office. He had three daughters, clearly cherished. Walls of his home are decorated with scores of photos taken over the years, from the time they were pigtailed little girls until they were young women in college graduation gowns. He ironed their clothes each day, Ernestine Lawrence recalls, and made his own starch solution to ensure crispness.

Red Lobster was his favorite restaurant, and vacation destinations were chosen by his daughters, who were encouraged to pick places they'd learned about in school. "We went to a lot of theme parks," Ernestine Lawrence recalls. No holiday – Easter, Thanksgiving, Halloween or Christmas – came without decorations that would put Clark Griswold to shame. Ernestine always held the ladder.

"You sure you've got it?" he asked about 20 years ago while he was stringing lights on the garage roof. "'I'm sure,'" Ernestine replied, hands firmly on the ladder, her feet safely on the ground. That's when the tilt started, and it didn't stop until both Archie and the ladder had fallen to earth, with Ernestine, also, taking a tumble as she struggled to save her husband from disaster. "We sat there and started laughing," Ernestine says. "The mailman saw it and came running over. When he saw we were OK, he started laughing, too." And so was born a Christmas tradition. "We'd talk about it every year: Would I let him fall off the roof?" Ernestine says.

During the 1980s, Lawrence, as NAACP president, joined a voting rights lawsuit filed against the city by McNeil and two others so that it could become a class-action matter that included the NAACP, as opposed to a case with only individuals as plaintiffs. Under the commissioner form of government then in place, no black person had been elected to run the city in more than 75 years. "He was so happy to be engaged in it," McNeil said.

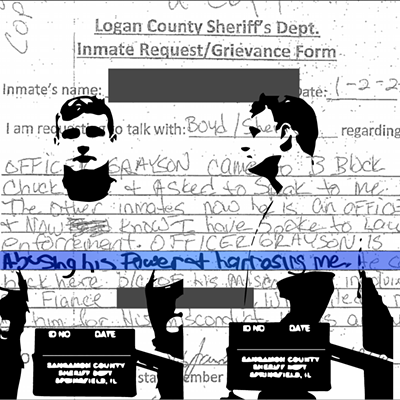

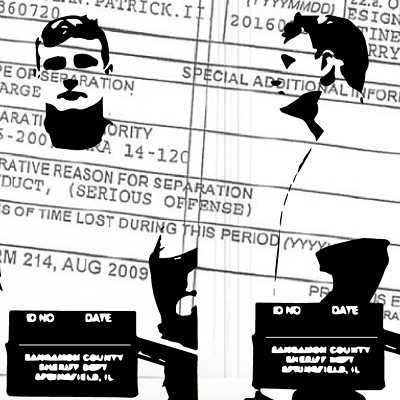

After the plaintiffs prevailed, Lawrence left his post as head of the NAACP and won a seat on the Sangamon County Board. In 2009, Lawrence, again, became president of the NAACP. He opposed consolidation of railroad tracks on 11th Street, arguing that the project would harm black neighborhoods. He objected to a proposed ordinance that would have allowed the city to impound cars for playing loud music on the grounds that cops might unfairly target black motorists. He called for the city to fire City Water, Light and Power employees for hanging nooses in their workplace.

When the city in 2010 received complaints about a Halloween yard display that featured a cowboy effigy hanging from a gallows, Lawrence and others concerned about racial overtones met with Josh Witkowski, the homeowner, who insisted it was innocent fun. Afterward, Lawrence agreed: "It was never his intent to have a racist prop in his yard – I am absolutely certain of that," Lawrence told the State Journal-Register. Witkowski altered the effigy's face to make clear it was not intended to depict a black person. Witkowski easily recalls the meeting, which included a discussion of classic jazz and Billie Holiday.

"He was very even, very calm, very cool, very thoughtful," Witkowski says. "We had a very open and honest conversation about who we were and where we came from. When you have somebody who comes from a position of engagement rather than conflict, it changes the outcome of a situation very quickly."

Lawrence's battle with cancer was prolonged. After he fell ill, he submitted his resignation as a trustee of Union Baptist Church, but the Rev. T. Ray McJunkins refused to accept it: If necessary, he told Lawrence, a phone would be set up at his bed so he could participate in meetings. He'd come to know Lawrence as a man who would sometimes question him privately about what was said from the pulpit, but not in a confrontational way. He recalls once getting so upset about something that he resigned as pastor, but Lawrence talked him out of it. He didn't know that McJunkins had received an offer from another church. "He said 'We have all this confidence in you and you're leaving us, but giving us no reason – that's not the way you do things, pastor,'" McJunkins recalls.

The church overflowed at Lawrence's funeral. Folks weren't surprised.

"First class guy, man – first class," McNeil says.