James A. Edstrom, Avenues of Transformation: Illinois' Path from Territory to State. Carbondale: Southern Illinois University Press, 2022. 250 pages, $26.50

It is always interesting to see why a person decided to write a book. The impetus for Avenues of Transformation came in 1987 when a patron asked librarian James A. Edstrom a question about the location originally proposed for the northern boundary of Illinois. Thirty-five years and countless hours of research and writing later, Edstrom thoroughly answers the question of how and why the northern boundary of Illinois did not end up at the southern tip of Lake Michigan.

Of course, the focus of this book is not on Illinois's northern border, but on a variety of personalities and issues that intersected in 1817-18 to bring about Illinois statehood. In particular, Edstrom focuses on three politicians with leading roles in the statehood process.

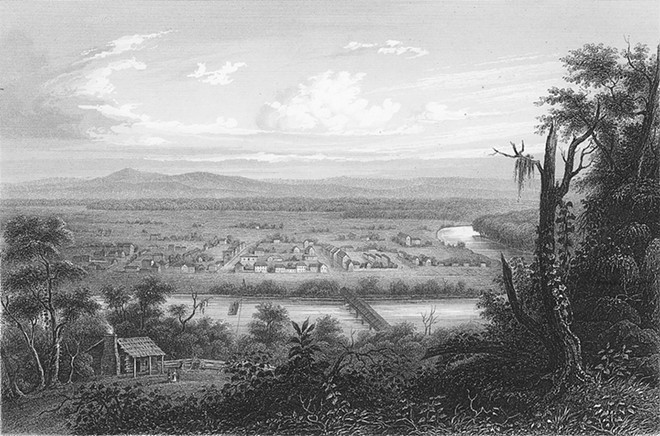

Daniel Pope Cook, a native of Kentucky who migrated to the Ste. Genevieve, Missouri/Kaskaskia, Illinois, area in 1811, promoted the idea of statehood in 1817 to resolve the perceived inadequacies of territorial government. Members of the territorial legislature prepared a petition to Congress requesting statehood and sent it to Nathaniel Pope, their territorial delegate in Washington, D.C. Pope received it in January 1818.

Pope, also from Kentucky, had moved to the Ste. Genevieve/Kaskaskia area in 1804. He became territorial secretary in 1809 when Illinois was split off from Indiana as a separate territory, and also served as acting governor when that official was absent. Now, as territorial delegate, Pope presented the petition to Congress, and was instrumental in getting that body to devise and pass a statehood enabling act for Illinois.

The third key politician was Elias Kent Kane, a native New Yorker and resident of Kaskaskia since 1814. Kane was the most influential member of the convention meeting in August 1818 to prepare a state constitution, managing discussion of the delicate questions. Although the three men represented several opposing political factions, all were determined to see Illinois become a state as speedily as possible.

Not surprisingly, the story of Illinois statehood is more complex than three prominent politicians. A number of other leaders, such as territorial governor Ninian Edwards, his enemy Jesse B. Thomas, and various members of the constitutional convention make their appearance.

Certain issues also had to be carefully considered and expressed in the statehood documents. The most critical of these was the matter of slavery. Although under the Northwest Ordinance of 1787, slavery was prohibited in the entire Northwest Territory, of which Illinois was a part, French settlers in the future Illinois had had slaves, and continued to hold them. Landowners who produced salt at the salines (salt springs) of Gallatin County, claimed that slaves were necessary laborers there and devised various indenture schemes to thwart restrictions.

Although many assumed that the Northwest Ordinance's prohibition of slavery at the territorial stage also meant prohibition at statehood, others argued that this was not necessarily the case. Some in the pro-slavery camp feared that Illinois' population growth would be stunted because slave owners would refuse to settle there if they could not bring their "property" with them. Ultimately, the state constitution made certain exceptions and left an opening for Illinois to become a slave state later (an option explored and discarded in 1824).

The matter of "internal improvements," particularly river and harbor improvements, canal construction, and the construction and maintenance of roads for postal purposes and interstate commerce, was a subject of hot debate during this period (and into the 1840s). State efforts at internal improvements were not the problem, but whether and to what extent the federal government might provide funding. Because of this controversy, the Illinois Constitution made limited requests for funding from public land sales.

The total population of Illinois was also a concern. The Northwest Ordinance specified a population of 60,000, with some exceptions, before a territory could become a state. However, recently Ohio and Mississippi had entered with considerably lower populations. Illinois politicians argued that their territory fit into the "general interest" of the country category, and should be admitted with a population of 40,000. The census taken in 1818 suggests padding to reach that number. However, authorities in Washington did not examine it too closely. Illinois became a state on Dec. 3, 1818.

Oh yes, about the northern boundary of Illinois. The statehood petition listed the prospective boundary as 10 miles north of the southern tip of Lake Michigan. Delegate Nathaniel Pope proposed the present boundary, about 51 miles north of that. His reasons were heavily economic, giving Illinois a shoreline and harbor with a lake connection to the upper North. In addition, with the proposed construction of what became the Illinois and Michigan Canal, Chicago could be expected to become a transportation hub with a water connection to the South as well. Furthermore, these transportation connections were predicted to be a potential source of national unity in case of sectional disagreements.

Anyone with an interest in early Illinois history will find this examination of the complexities of the statehood process to be an informative and worthwhile read.

As a former manuscripts librarian at several institutions, Springfield historian Glenna R. Schroeder-Lein knows from personal experience how a patron question can inspire research projects.