Plasma is already widely used for a variety of life-saving medical procedures, and it's now being tried as a possible means of treating COVID-19 patients. However, plasma cannot be reproduced in a lab – only the human body can produce it. That means identifying willing donors, and in the U.S., paying for plasma as a means of incentivizing donors.

A booming business

Plasma is big business, with blood products accounting for more than 1.9% of American exports in 2016, more than soybeans or computers ("What is the blood of a poor person worth?," New York Times, Feb. 1, 2019). For this reason, the U.S. is often referred to as the OPEC of plasma.

Globally, plasma is currently a $26 billion industry, with the market growing 6-10% yearly. According to a recent ProPublica report, the United States had more than 800 plasma centers at the end of 2019, with more being built regularly. This trend also holds true in Springfield, with two for-profit plasma centers currently under construction, in addition to an existing privately owned plasma business.

Octapharma Plasma, a Swiss biopharmaceutical company, has had a presence in Springfield for years; it's been located at 1770 Wabash Ave. in the Chatham Square shopping center since 2013. Octapharma will soon be joined by two other plasma centers.

The former Aldi location in the Near North Crossing shopping center, 1150 N. Fifth St., is being remodeled for a new tenant, CSL Plasma. The company is a division of CSL Behring, headquartered in Pennsylvania, although the parent company, CSL Limited, is headquartered in Australia.

CSL Plasma will initially employ 20-25 people but plans to grow to a staff of 60 or more, according to divisional director Scott Newkirk. "Positions include leadership positions in management and quality, medical staff, phlebotomists and donor screening," he said.

KEDPLASMA USA, a subsidiary of Italian company Kedrion Biopharma, announced earlier this year it will break ground for a new facility near the intersection of North Grand Avenue and Walnut Street, next to DaVita Dialysis, with an anticipated opening in January 2021. Earlier this year, the Springfield City Council approved a zoning change to the nearly two acres of land to allow for construction of an 11,900-square-foot office building.

Both new facilities, less than a mile apart, will be located within the boundaries of the Mid-Illinois Medical District.

Forrest McCaleb, director of global communications for Kedrion Biopharma, said that when searching for a new location, the company tends to stick to smaller communities like Springfield.

"Kedrion is a family-owned business, and we like to see family values reflected where we are," McCaleb said. Although Kedrion is an international company established in Italy in 2001, the roots of the companies from which it was born stretch back several decades in the production of blood and plasma-derived products.

Additionally, he said, Kedrion takes into consideration the age of the population and viral marker rates for diseases that would exclude a donor, such as HIV and hepatitis A and B. According to McCaleb, the company will employ 40-45 people once the facility opens.

Scott Stough, chief operating officer at The Stough Group, the development company responsible for building and managing Kedrion's new facilities, noted the site in Springfield is in close proximity to the medical facilities. Stough is the third generation of the family business, which now focuses on real estate development for plasma centers, having sold off the operations side of the business in 2006 to an international company.

In a February interview with Springfield Business Journal, Stough said, "Due to the working-class population and demographics of Springfield, we felt that it would be ideal to not only be in the medical district but to be an asset to the community and grow the footprint of the medical district onto North Grand."

Stough Development Corporation, based in Cincinnati, Ohio, has built plasma centers in 17 states and has projects underway in Lincoln, Nebraska; Jacksonville, Florida; Mobile, Alabama; and Augusta, Georgia, along with three in Illinois. In addition to Springfield, the company is currently building new centers in Champaign and Joliet.

Plasma and the donation process

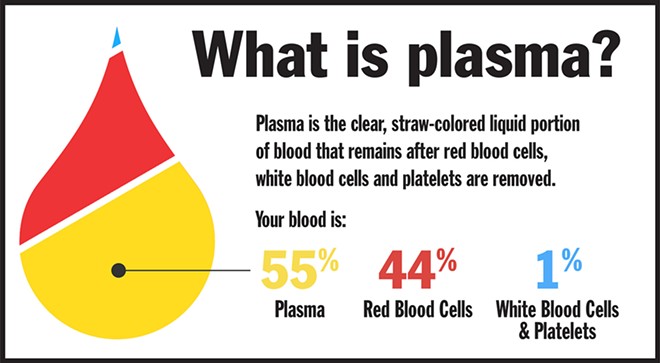

Plasma makes up one of four parts of the blood, the other three being red blood cells, white blood cells and platelets. Plasma is largely composed of water, but is also a rich source of proteins, clotting agents, albumin and immunoglobulins (antibodies), making it an ideal treatment for hemophilia and other clotting disorders, immunodeficiency diseases, neurological conditions and genetic disorders. Additionally, plasma is used to support critical care procedures such as surgeries, burns and organ transplants and is being investigated for its possible use in treating severely affected COVID-19 patients.

Plasma cannot be reproduced in a lab, nor acquired from any source but human blood. As a result, plasma donations are a necessary component of plasma-derived medicinal products (PDMPs). Plasma obtained from paid donors in the United States makes up 70% of the global supply of plasma and 90% of paid plasma donations worldwide, mostly because of the less-stringent restrictions and payment process of American plasma centers.

A paid plasma donor in the United States must be between 18 and 59 years of age, weigh at least 110 pounds and be in good overall health. Identification such as a driver's license, proof of Social Security number and address are required, and the donor must reside in the area, in an effort to exclude homeless or transient donors.

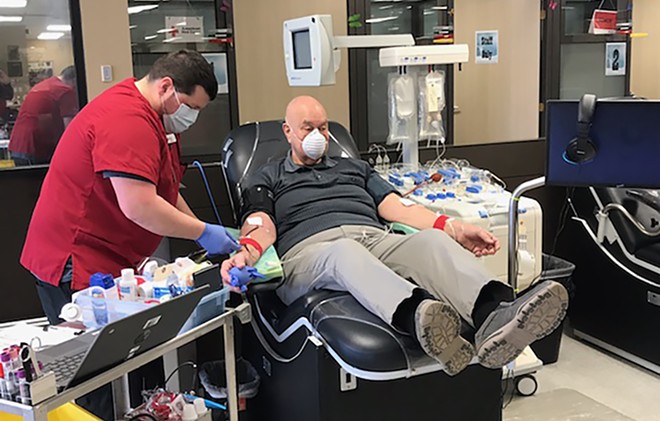

McCaleb provided some insights as to what to expect during the donation process. On the first visit, a potential donor will complete a pre-screening process, answering questions about health and lifestyle choices. Then vitals and weight will be taken, as the amount of plasma donated is determined by the weight of the donor. The donor will then be taken back to the donation area for the plasmapheresis process, which begins with a needle inserted into the arm to extract whole blood. The plasma is separated through centrifuging and then the remaining parts of the blood, sans plasma, are returned to the donor in a completely sterile and automated process.

After being given 500 ml of saline to replace the extracted plasma, the donor is compensated via a preloaded debit card, made aware of referral and rewards programs and then discharged. The process for a first-time donor takes a little more than two hours, with subsequent visits of 30-60 minutes, though the wait to donate may take significantly longer.

New donors are incentivized and can receive as much as $400 the first month due to first-time donor bonuses. A regular donor can expect compensation ranging from $280 to $350 per month, depending on the donation center. In the United States, plasma may be donated twice within a seven-day period, with at least one day between donations. Otherwise, there is no limit on the number of donations, meaning a donor could potentially give plasma 104 times a year for consecutive years.

After plasma is donated, it is immediately frozen and stored, with samples sent out for testing for various blood-borne diseases. If deemed safe, the accumulated plasma is sent to a fractionation facility where it is separated into the different components from which PDMPs are made, usually into injectable treatments, which are then distributed worldwide. The U.S. receives approximately 40% of the global share of PDMPs, so much of the plasma collected in the U.S. is actually put to use in other countries.

Plasma donation centers follow Centers for Disease Control and Prevention guidelines for safety, with additional precautions now taken during the pandemic. Adhering to strict cleaning protocols, staff wear face shields and take the temperature of anyone entering the building. Masks for donors are required. Beds for donation and chairs in the waiting room are socially distanced and, when at capacity, donors are encouraged to wait in their cars until their name is called.

Poverty clouds the process

Though it saves countless lives, paid plasma donation is not without its critics. The twice-weekly collection schedule allowed in the United States is not routine in most parts of Europe, where donors are not compensated – though countries such as Italy may offer a paid vacation day to donors – and are limited to once every two weeks. Critics assert that poverty is the main driver in paid plasma donation, not altruism, and that donors may be risking their health with frequent donations in exchange for quick cash. According to a 2017 study by ABC News, nearly 80% of U.S. plasma centers are located in low-income neighborhoods.

The process is designed to accept only healthy donors, but it is possible to cheat the pre-screening process. Some homeless people get around the address requirement by having a local mailing address where they collect mail but do not live. Underweight donors may wear ankle weights to qualify. Others outright lie about lifestyle and health to pass through the process. Lured by the opportunity to make quick money, others are addicts, mentally ill or disguise health conditions in order to be able to donate for much-needed cash.

Dr. Lucy Reynolds, a research fellow at the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, told The Atlantic that, "Certain governments are people- and people's rights-centered. In those places they make the plasma corporations play by the rules; sometimes they just choose to have as little as possible to do with them. But the United States is a corporate country," noting that the U.S. maintains the least restrictive plasma donation regulations in the world ("The Twisted Business of Donating Plasma," May 28, 2014).

This lack of regulations, some assert, can lead to disastrous consequences for individual donors. A Springfield-area paramedic, who spoke on the condition of anonymity due to her employment, said that she treats patients with side effects of plasma donation, on average, about once a month. "Usually it's from low blood pressure, lightheadedness, dizziness and feeling faint," she said.

Though donors are instructed to return to the plasma center if they experience a medical need, "It's often a bystander who calls, or someone with them," reports the paramedic, explaining there's usually not time to return to the plasma center, as many lose consciousness. Other donors simply do not want the plasma center to know they are having medical issues, for fear that this will interfere with their next donation cycle. The paramedic said most of the cases she sees are taken to the hospital for care and usually revived with a full panel of electrolytes while their vitals are monitored.

A fellow paramedic, who also spoke on the condition of anonymity, noted, "We don't really see the healthy people who donate, only the ones who are having issues from donating. For you and me, it wouldn't be a problem because we can replenish ourselves. But a lot of the homes we go into, there's nothing to eat, nothing in the cabinets. They just don't have the means to replenish their bodies."

A complicated history

The history of the use of blood products has been problematic at times, with diseases shared between those who give and those who receive blood products, including plasma. Many have died, although increased safety standards have been implemented as a result.

Hemophilia, a genetic disorder which currently affects about 20,000 Americans, prevents blood from clotting normally. This can cause a hemophiliac to bleed longer after an injury, and over the course of a year, treatment of one severe hemophiliac may require 1,200 units of plasma, each unit the result of a single plasma donation session.

Nearly half of American hemophiliacs (and roughly 90% of severe hemophiliacs) contracted HIV in the early 1980s from contaminated blood products, resulting in approximately 4,000 patients eventually dying from AIDS. At the time, donations were largely sourced from the U.S. prison population. A class-action lawsuit filed by hemophiliacs and their families presented evidence that even after the discovery of tainted blood products, a major plasma company continued to distribute its older supplies. However, due to federal and state protections, plasma corporations were not penalized.

In the early to mid-1990s, China implemented its "Plasma Economy," offering poor Chinese farmers payment for plasma donations. Due to low standards for safety and sanitation, equipment was routinely reused and collected blood was pooled before plasma was extracted, with shared blood being pumped back into individual donors. About 40% of donors contracted HIV and/or hepatitis, and more than a million rural Chinese citizens died as a result. This health crisis was suppressed by the Chinese government, as well as the business middlemen who reaped the financial benefits.

In the wake of these scandals, the Plasma Protein Therapy Association (PPTA) was formed in the 1990s. PPTA is a global organization representing the plasma donation and therapies industry, which "administers standards and programs that help ensure the quality and safety of plasma collection and manufacturing and protect both donors and patients." PPTA's goals include ensuring a safe process for the donation and collection of plasma while addressing the broad range of issues arising from the dynamic international plasma market.

PPTA has developed a voluntary International Quality Plasma Program that serves as a third-party evaluator for members of PPTA, designed to ensure a safe environment for donors and maintain standards for plasma centers.

In an interview with IT, PPTA director of global communications Mat Gulick asserted, "The increases in awareness and capability of testing have resulted in a completely safe blood supply," noting that there has been no transmission of disease among those receiving injectable plasma treatments for nearly 30 years.

Plasma and COVID-19

The American Red Cross (ARC) and other nonprofit blood centers also take plasma donations, but on a strictly unpaid basis. A rest period of 28 days is required between donations. Plasma from donors is not separated and processed into medications, but is sent "directly to hospital partners for use in emergency situations," explained Laura McGuire, external communications manager for Red Cross Illinois Blood Services.

All blood donations, including donations for plasma, have decreased significantly due to the coronavirus pandemic, as sites which normally host blood drives have closed or have limited operations. McGuire stressed that additional safety practices have been put into place at collection sites for volunteers, staff and donors. In addition to temperature checks and screening questions, beds are distanced and appointment times are staggered to lessen capacity.

While ARC does not test for COVID-19, all blood donations are screened for the antibodies, and donors are informed if antibodies are present. Data is anonymous, but health organizations receive data on the number of positive and negative tests for antibodies, which helps give a clearer picture of the extent of COVID-19 spread in communities.

According to McGuire, the Red Cross was approached by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration to create a system to collect convalescent plasma, which is plasma from donors who have a confirmed diagnosis for COVID-19 and have been free of symptoms for 28 days.

"We're all about helping people," McGuire said. "We turned the concept into a process in a very short time. The ARC really stepped up, and in a month, we had it set up."

While no studies have definitively shown that convalescent plasma is a cure, there have been positive initial signs in hospitals where convalescent plasma has been used to treat COVID-19 patients. Convalescent plasma can be frozen for up to a year, and its use as a therapy assists the ongoing studies and search for data related to the novel coronavirus.

Academic institutions, for-profit plasma centers and national blood organizations have now partnered in an international effort to encourage those who have survived COVID-19 to donate plasma, with Dwayne "The Rock" Johnson serving as a spokesman.

Show me the money

The recession of 2008 brought a wave of donors to plasma centers, and it is expected that the financial repercussions of the COVID-19 pandemic will do likewise as the U.S. continues to grapple with record levels of unemployment. While the World Health Organization has long taken a stance against compensating plasma donors, some argue this concern is outdated. Peter Jaworski, a professor of ethics at Georgetown University's McDonough School of Business, makes a case that other countries should begin compensating plasma donors, particularly as the need for convalescent plasma increases and the number of donors – both paid and unpaid – has dropped off since the pandemic began ("Americans get paid to donate plasma, everyone else should too," Reason, July 2, 2020). He notes that when the Czech Republic legalized compensation for plasma donors in 2008, donations increased sevenfold over the next three years, with no impact on unpaid donations.

Currently, 5% of the world's population provides more than half of the world's plasma, with just five countries – the U.S. and four European countries that allow plasma donors to receive payment – accounting for 90% of the world's plasma. Jaworski and others believe this is not a sustainable model, pointing to COVID-19 as an example of a supply chain disruption that has reduced the amount of plasma available as the need has continued to increase.

Don, a regular donor for two years, is a stay-at-home father in Springfield who asked that his last name not be used due to the stigma associated with plasma donation. Don said his main drive was the need for extra money until he was able to re-enter the workforce.

"It was nice being able to do it more or less on my own schedule, and fit it in on a morning or afternoon when it worked best for my family. I had thought that it was something only desperate junkies do, but the people there donating were mostly regular people," he said.

Don suggests donors bring music and a book to pass the time, as there is often a wait if many donors are already in line upon arrival. As far as recommending plasma donation, he said, "If you need some extra money, and have the time, it's worth it."

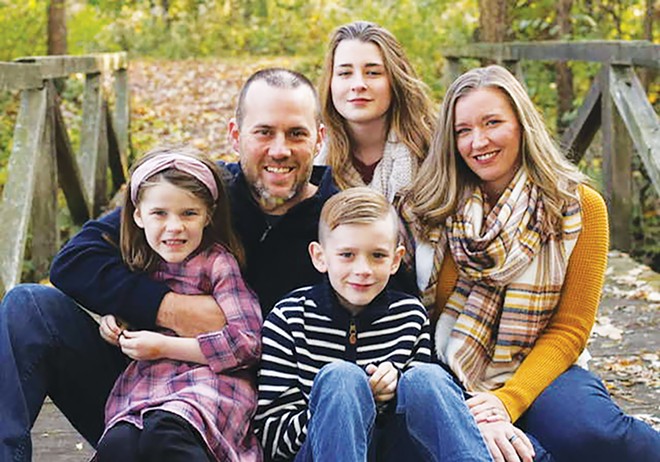

Melissa Blevins, a former Springfield resident who now lives in Florida, previously worked in banking and real estate, but donated plasma over an 18-month period while staying at home with her children. While her younger brother had donated plasma in college for beer money, Blevins had a different aim. She and her husband donated together, earning up to $800 per month and using the extra income to pay off debts and pay for sports programs for their kids that they couldn't otherwise afford.

Her personal finance blog, perfectionhangover.com, features a variety of suggestions for women who are seeking extra income, either to supplement or replace employment outside the home, including a documentation of her own plasma donation experience. Though she's now been able to replace her plasma donations with monetized blogging and YouTube videos, Blevins recommends plasma donation.

"For someone who is digging through the couch cushions to find money for their next meal, or has massive debt, or just wants to have a little extra money to fund their child's sports program needs or to save for a vacation, plasma donation is a good way to go," she said.

Blevins admits she did feel out of place in the plasma center, but says she found out that most of the staff donated too. "They'll stay after their shift, or come in early. I think it's so the people who donate will see that it's so safe and recommended that even the staff do it."

She did experience feeling tired or weak after donation, and Blevins said she found she had to get her cardio workout in prior to donating. She also still has puncture scarring on her arms from the needles, despite switching donation arms on every visit. "I look like a drug addict," Blevins said, even after two-and-half years of not donating.

"I still recommend it, though. You have to overlook the stigma and the negative comments. You're saving lives by donating plasma. You're earning extra money for what's important to you. It's worth it."

Carey Smith is a Springfield mother and gardener with a keen interest in the issues of poverty.