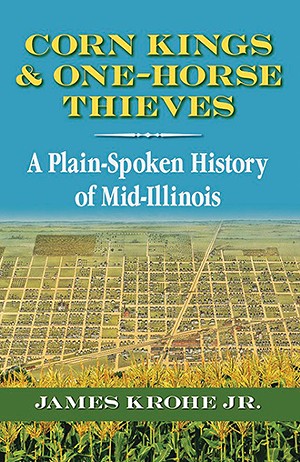

Look at what I had to leave out about Carlinville. Gideon Blackburn is mentioned in connection with his setting up the public land company whose profits were to endow the theological seminary that, after his death, was named after him (and later renamed Blackburn College). But do-gooder Blackburn was a man of many parts. This Presbyterian minister also was a surveyor and distiller (and, possibly, bootlegger). He was a missionary who set up a school in Tennessee to turn Creek and Cherokee boys into cultured men, even though most of them believed they already were cultured men. A Cherokee accommodationist whom Blackburn sheltered was killed by his fellow tribesmen as disloyal, which caused Blackburn to get out of the culture business and come to Illinois, where no one presumed to think of themselves as cultured.

An altogether more admirable Carlinvillian was John McAuley Palmer. Springfield named a public school on the near east side after Palmer, and Palmer is one of the men memorialized in bronze on the east lawn of the Statehouse, but few know of him today. Palmer was a capable Civil War general in the Civil War. Wikipedia in fact describes him as a soldier, but Palmer also served with distinction as Illinois governor and U.S. senator, and was a plausible candidate for the presidency in 1892. He was intelligent, honest, brave, principled and – his saving grace – had a sense of humor. Palmer also was a personal and political intimate of Lincoln who played a part in winning for his friend the Republican nomination in 1860.

Much harder than any of that, he was a decent memoirist. My book is about Illinois, and only to that extent about Illinoisans, so I was obliged to pass up the chance to repeat (as many others have repeated before me) this anecdote from his memoir. In 1865 he met at the White House with Lincoln. The war was being won, and Palmer dared to josh the president. “Mr. Lincoln, if I had known at Chicago that this great rebellion was to occur, I would not have consented to go to a one-horse town like Springfield, and take a one-horse lawyer, and make him president.” (As Palmer would recollect, Lincoln replied, “Neither would I, Palmer [but] if we had had a great man for the presidency, one who had an inflexible policy and stuck to it, this rebellion would have succeeded . . . .”)

Carlinville also is remarkable in having built a splendiferous monument to its own folly. At its opening in 1870, the Macoupin County courthouse there was the largest courthouse in the country outside of New York City. (The newly wed John Palmer, as it happened, lived in a log house that stood on the building’s future site.) It was larger than the then-Illinois Statehouse, and possessing it put Carlinville in the running as a new state capital when the State of Illinois decided that its Statehouse in Springfield was too small.

The courthouse was a capitol, in effect, of what some locals still derisively call the “Great State of Macoupin.” A building initially budgeted at $50,000 ended up costing nearly $1.5 million in borrowed money. Some regarded this as extravagant; Macoupin’s first courthouse, built in 1829 of hewn logs with one window, had cost $44.33.

When the cornerstone was laid there was placed in it proceedings of the court case brought by people seeking to enjoin the county court from building it. Backers of the project obtained a special state act that authorized the courthouse commission to levy whatever tax was needed to pay the bills, they having a friend in the Statehouse in the person of Palmer, who’d been elected governor in 1868. When the final paid-off bond was ceremonially burned in the courthouse square in 1910, the crowd sang two stanzas of “America” and every bell and whistle in every town in Macoupin County sounded for five minutes.

Sadly, the courthouse saga does not figure in my book either. The merely interesting is always giving way to the important. Some will argue whether that improves histories – I’ve argued it myself – but there is no disputing that it frustrates historians. One turns back to newspaper writin’ about the Springfield of 2017, where that choice never needs to be made.

Contact James Krohe Jr. at [email protected].